Chapter 4. Encoding and Evolution

When a data format or schema changes, a corresponding change to application code often needs to happen. However, in a large application, code changes often cannot happen instantaneously:

-

With server-side applications you may want to perform a rolling upgrade, deploying the new version to a few nodes at a time, checking whether the new version is running smoothly, and gradually working your way through all the nodes. This allows new versions to be deployed without service downtime, and thus encourages more frequent releases and better evolvability.

-

With client-side applications you’re at the mercy of the user, who may not install the update for some time.

This means that old and new versions of the code, and old and new data formats, may potentially all coexist in the system at the same time. In order for the system to continue running smoothly, we need to maintain compatibility in both directions:

-

Backward compatibility: Newer code can read data that was written by older code.

-

Forward compatibility: Older code can read data that was written by newer code.

In this chapter we will look at several formats for encoding data, including JSON, XML, Protocol Buffers, Thrift, and Avro. In particular, we will look at how they handle schema changes and how they support systems where old and new data and code need to coexist. We will then discuss how those formats are used for data storage and for communication: in web services, Representational State Transfer (REST), and remote procedure calls (RPC), as well as message-passing systems such as actors and message queues.

Formats for Encoding Data

Programs usually work with data in (at least) two different representations:

-

In memory, data is kept in objects, structs, lists, arrays, hash tables, trees, and so on. These data structures are optimized for efficient access and manipulation by the CPU (typically using pointers).

-

When you want to write data to a file or send it over the network, you have to encode it as some kind of self-contained sequence of bytes (for example, a JSON document). Since a pointer wouldn’t make sense to any other process, this sequence-of-bytes representation looks quite different from the data structures that are normally used in memory.

Thus, we need some kind of translation between the two representations. The translation from the in-memory representation to a byte sequence is called encoding (also known as serialization or marshalling), and the reverse is called decoding (parsing, deserialization, unmarshalling).

Language-Specific Formats

Many programming languages come with built-in support for encoding in-memory objects into byte sequences. However, they also have a number of deep problems:

-

The encoding is often tied to a particular programming language, and reading the data in another language is very difficult.

-

In order to restore data in the same object types, the decoding process needs to be able to instantiate arbitrary classes. This is frequently a source of security problems: if an attacker can get your application to decode an arbitrary byte sequence, they can instantiate arbitrary classes, which in turn often allows them to do terrible things such as remotely executing arbitrary code.

-

Versioning data is often an afterthought in these libraries: as they are intended for quick and easy encoding of data, they often neglect the inconvenient problems of forward and backward compatibility.

-

Efficiency (CPU time taken to encode or decode, and the size of the encoded structure) is also often an afterthought.

For these reasons it’s generally a bad idea to use your language’s built-in encoding for anything other than very transient purposes.

JSON, XML, and Binary Variants

JSON, XML, and CSV are textual formats, and thus somewhat human-readable. Besides the superficial syntactic issues, they also have some subtle problems:

-

There is a lot of ambiguity around the encoding of numbers. This is a problem when dealing with large numbers; for example, integers greater than 253 cannot be exactly represented in an IEEE 754 double-precision floating-point number, so such numbers become inaccurate when parsed in a language that uses floating-point numbers.

-

JSON and XML have good support for Unicode character strings (i.e., human- readable text), but they don’t support binary strings (sequences of bytes without a character encoding). Binary strings are a useful feature, so people get around this limitation by encoding the binary data as text using Base64. This works, but it’s somewhat hacky and increases the data size by 33%.

Thrift and Protocol Buffers

Both Thrift and Protocol Buffers require a schema for any data that is encoded.

Modes of Dataflow

In this chapter we will explore some of the most common ways how data flows between processes:

- Via databases

- Via service calls

- Via asynchronous message passing

Dataflow Through Databases

Backward compatibility is clearly necessary here; otherwise your future self won’t be able to decode what you previously wrote.

A value in the database may be written by a newer version of the code, and subsequently read by an older version of the code that is still running. Thus, forward compatibility is also often required for databases.

If you decode a database value into model objects in the application, and later reencode those model objects, the unknown field might be lost in that translation process. Solving this is not a hard problem; you just need to be aware of it.

Dataflow Through Services: REST and RPC

There are two popular approaches to web services: REST and SOAP. They are almost diametrically opposed in terms of philosophy.

REST is not a protocol, but rather a design philosophy that builds upon the principles of HTTP. It emphasizes simple data formats, using URLs for identifying resources and using HTTP features for cache control, authentication, and content type negotiation. An API designed according to the principles of REST is called RESTful.

By contrast, SOAP is an XML-based protocol for making network API requests. Although it is most commonly used over HTTP, it aims to be independent from HTTP and avoids using most HTTP features.

The API of a SOAP web service is described using an XML-based language called the Web Services Description Language, or WSDL. WSDL enables code generation so that a client can access a remote service using local classes and method calls. This is useful in statically typed programming languages, but less so in dynamically typed ones.

RESTful APIs tend to favor simpler approaches, typically involving less code generation and automated tooling.

Data encoding and evolution for RPC

The RPC model tries to make a request to a remote network service look the same as calling a function or method in your programming language, within the same process (this abstraction is called location transparency).

It is reasonable to assume that all the servers will be updated first, and all the clients second. Thus, you only need backward compatibility on requests, and forward compatibility on responses.

The backward and forward compatibility properties of an RPC scheme are inherited from whatever encoding it uses.

Service compatibility is made harder by the fact that RPC is often used for communication across organizational boundaries, so the provider of a service often has no control over its clients and cannot force them to upgrade. Thus, compatibility needs to be maintained for a long time, perhaps indefinitely.

Message-Passing Dataflow

Asynchronous message-passing systems are similar to RPC in that a client’s request (usually called a message) is delivered to another process with low latency. They are similar to databases in that the message is not sent via a direct network connection, but goes via an intermediary called a message broker (also called a message queue or message-oriented middleware), which stores the message temporarily.

Using a message broker has several advantages compared to direct RPC:

- It can act as a buffer if the recipient is unavailable or overloaded, and thus improve system reliability.

- It can automatically redeliver messages to a process that has crashed, and thus prevent messages from being lost.

- It avoids the sender needing to know the IP address and port number of the recipient (which is particularly useful in a cloud deployment where virtual machines often come and go).

- It allows one message to be sent to several recipients.

- It logically decouples the sender from the recipient (the sender just publishes messages and doesn’t care who consumes them).

However, a difference compared to RPC is that message-passing communication is usually one-way: a sender normally doesn’t expect to receive a reply to its messages. It is possible for a process to send a response, but this would usually be done on a separate channel. This communication pattern is asynchronous: the sender doesn’t wait for the message to be delivered, but simply sends it and then forgets about it.

Distributed actor frameworks

The actor model is a programming model for concurrency in a single process. Rather than dealing directly with threads (and the associated problems of race conditions, locking, and deadlock), logic is encapsulated in actors. Each actor typically represents one client or entity, it may have some local state (which is not shared with any other actor), and it communicates with other actors by sending and receiving asynchronous messages. Since each actor processes only one message at a time, it doesn’t need to worry about threads, and each actor can be scheduled independently by the framework.

In distributed actor frameworks, this programming model is used to scale an application across multiple nodes. The same message-passing mechanism is used, no matter whether the sender and recipient are on the same node or different nodes. If they are on different nodes, the message is transparently encoded into a byte sequence, sent over the network, and decoded on the other side.

Summary

Many services need to support rolling upgrades, where a new version of a service is gradually deployed to a few nodes at a time, rather than deploying to all nodes simultaneously. Rolling upgrades allow new versions of a service to be released without downtime. These properties are hugely beneficial for evolvability, the ease of making changes to an application.

During rolling upgrades, or for various other reasons, we must assume that different nodes are running the different versions of our application’s code. Thus, it is important that all data flowing around the system is encoded in a way that provides backward compatibility (new code can read old data) and forward compatibility (old code can read new data).

Chapter 5. Replication

There are various reasons why you might want to distribute a database across multiple machines:

-

Scalability

If your data volume, read load, or write load grows bigger than a single machine can handle, you can potentially spread the load across multiple machines.

-

Fault tolerance/high availability

If your application needs to continue working even if one machine (or several machines, or the network, or an entire datacenter) goes down, you can use multiple machines to give you redundancy. When one fails, another one can take over.

-

Latency

If you have users around the world, you might want to have servers at various locations worldwide so that each user can be served from a datacenter that is geographically close to them. That avoids the users having to wait for network packets to travel halfway around the world.

Replication means keeping a copy of the same data on multiple machines that are connected via a network. There are several reasons why you might want to replicate data:

- To keep data geographically close to your users (and thus reduce latency)

- To allow the system to continue working even if some of its parts have failed (and thus increase availability)

- To scale out the number of machines that can serve read queries (and thus increase read throughput)

We will discuss three popular algorithms for replicating changes between nodes: single-leader, multi-leader, and leaderless replication.

Leaders and Followers

Each node that stores a copy of the database is called a replica. Every write to the database needs to be processed by every replica. The most common solution for this is called leader-based replication (also known as active/passive or master–slave replication):

-

One of the replicas is designated the leader (also known as master or primary). When clients want to write to the database, they must send their requests to the leader, which first writes the new data to its local storage.

-

The other replicas are known as followers (read replicas, slaves, secondaries, or hot standbys). Whenever the leader writes new data to its local storage, it also sends the data change to all of its followers as part of a replication log or change stream. Each follower takes the log from the leader and updates its local copy of the database accordingly, by applying all writes in the same order as they were processed on the leader.

-

When a client wants to read from the database, it can query either the leader or any of the followers. However, writes are only accepted on the leader (the followers are read-only from the client’s point of view).

Synchronous Versus Asynchronous Replication

Often, leader-based replication is configured to be completely asynchronous. In this case, if the leader fails and is not recoverable, any writes that have not yet been replicated to followers are lost. This means that a write is not guaranteed to be durable.

Setting Up New Followers

- Take a consistent snapshot of the leader’s database at some point in time—if possible, without taking a lock on the entire database. Most databases have this feature, as it is also required for backups.

- Copy the snapshot to the new follower node.

- The follower connects to the leader and requests all the data changes that have happened since the snapshot was taken. This requires that the snapshot is associated with an exact position in the leader’s replication log.

- When the follower has processed the backlog of data changes since the snapshot, we say it has caught up. It can now continue to process data changes from the leader as they happen.

Handling Node Outages

How do you achieve high availability with leader-based replication?

Follower failure: Catch-up recovery

The follower can recover quite easily: from its log, it knows the last transaction that was processed before the fault occurred. Thus, the follower can connect to the leader and request all the data changes that occurred during the time when the follower was disconnected.

Leader failure: Failover

Handling a failure of the leader is trickier: one of the followers needs to be promoted to be the new leader, clients need to be reconfigured to send their writes to the new leader, and the other followers need to start consuming data changes from the new leader. This process is called failover.

Failover can happen manually or automatically. An automatic failover process usually consists of the following steps:

- Determining that the leader has failed.

- Choosing a new leader.

- Reconfiguring the system to use the new leader.

Implementation of Replication Logs

Statement-based replication

In the simplest case, the leader logs every write request (statement) that it executes and sends that statement log to its followers.

There are various ways in which this approach to replication can break down:

-

Any statement that calls a nondeterministic function, such as NOW() to get the current date and time or RAND() to get a random number, is likely to generate a different value on each replica.

-

If statements use an autoincrementing column, or if they depend on the existing data in the database (e.g., UPDATE … WHERE

), they must be executed in exactly the same order on each replica, or else they may have a different effect. This can be limiting when there are multiple concurrently executing transactions. -

Statements that have side effects (e.g., triggers, stored procedures, user-defined functions) may result in different side effects occurring on each replica, unless the side effects are absolutely deterministic.

Statement-based replication was used in MySQL before version 5.1.

Write-ahead log (WAL) shipping

In Chapter 3 we discussed how storage engines represent data on disk, and we found that usually every write is appended to a log. In either case, the log is an append-only sequence of bytes containing all writes to the database. We can use the exact same log to build a replica on another node: besides writing the log to disk, the leader also sends it across the network to its followers. When the follower processes this log, it builds a copy of the exact same data structures as found on the leader.

The main disadvantage is that the log describes the data on a very low level: a WAL contains details of which bytes were changed in which disk blocks. This makes replication closely coupled to the storage engine. If the database changes its storage format from one version to another, it is typically not possible to run different versions of the database software on the leader and the followers.

Logical (row-based) log replication

An alternative is to use different log formats for replication and for the storage engine, which allows the replication log to be decoupled from the storage engine internals. This kind of replication log is called a logical log, to distinguish it from the storage engine’s (physical) data representation.

A logical log for a relational database is usually a sequence of records describing writes to database tables at the granularity of a row:

- For an inserted row, the log contains the new values of all columns.

- For a deleted row, the log contains enough information to uniquely identify the row that was deleted. Typically this would be the primary key, but if there is no primary key on the table, the old values of all columns need to be logged.

- For an updated row, the log contains enough information to uniquely identify the updated row, and the new values of all columns (or at least the new values of all columns that changed).

A transaction that modifies several rows generates several such log records, followed by a record indicating that the transaction was committed. MySQL’s binlog (when configured to use row-based replication) uses this approach.

Trigger-based replication

The replication approaches described so far are implemented by the database system, without involving any application code. If you want to only replicate a subset of the data, or want to replicate from one kind of database to another, or if you need conflict resolution logic, then you may need to move replication up to the application layer.

An alternative is to use features that are available in many relational databases: triggers and stored procedures.

A trigger lets you register custom application code that is automatically executed when a data change (write transaction) occurs in a database system.

Problems with Replication Lag

Being able to tolerate node failures is just one reason for wanting replication. Other reasons are scalability (processing more requests than a single machine can handle) and latency (placing replicas geo‐graphically closer to users).

Leader-based replication requires all writes to go through a single node, but read-only queries can go to any replica.

However, this approach only realistically works with asynchronous replication—if you tried to synchronously replicate to all followers, a single node failure or network outage would make the entire system unavailable for writing.

Unfortunately, if an application reads from an asynchronous follower, it may see outdated information if the follower has fallen behind.

This inconsistency is just a temporary state—if you stop writing to the database and wait a while, the followers will eventually catch up and become consistent with the leader. For that reason, this effect is known as eventual consistency.

Reading Your Own Writes

Read-after-write consistency, also known as read-your-writes consistency, is a guarantee that if the user reloads the page, they will always see any updates they submitted themselves.

There are various possible techniques to implement read-after-write consistency in a system with leader-based replication:

-

When reading something that the user may have modified, read it from the leader; otherwise, read it from a follower. This requires that you have some way of knowing whether something might have been modified, without actually querying it.

-

If most things in the application are potentially editable by the user, that approach won’t be effective, as most things would have to be read from the leader.

-

The client can remember the timestamp of its most recent write—then the system can ensure that the replica serving any reads for that user reflects updates at least until that timestamp. If a replica is not sufficiently up to date, either the read can be handled by another replica or the query can wait until the replica has caught up. The timestamp could be a logical timestamp (something that indicates ordering of writes, such as the log sequence number) or the actual system clock.

-

If your replicas are distributed across multiple datacenters (for geographical proximity to users or for availability), there is additional complexity. Any request that needs to be served by the leader must be routed to the datacenter that contains the leader.

Another complication arises when the same user is accessing your service from multiple devices, in this case, there are some additional issues to consider:

-

Approaches that require remembering the timestamp of the user’s last update become more difficult, because the code running on one device doesn’t know what updates have happened on the other device. This metadata will need to be centralized.

-

If your replicas are distributed across different datacenters, there is no guarantee that connections from different devices will be routed to the same datacenter. If your approach requires reading from the leader, you may first need to route requests from all of a user’s devices to the same datacenter.

Monotonic Reads

Our second example of an anomaly that can occur when reading from asynchronous followers is that it’s possible for a user to see things moving backward in time.

Monotonic reads is a guarantee that this kind of anomaly does not happen. It’s a lesser guarantee than strong consistency, but a stronger guarantee than eventual consistency. When you read data, you may see an old value; monotonic reads only means that if one user makes several reads in sequence, they will not see time go backward.

One way of achieving monotonic reads is to make sure that each user always makes their reads from the same replica. However, if that replica fails, the user’s queries will need to be rerouted to another replica.

Consistent Prefix Reads

Our third example of replication lag anomalies concerns violation of causality. Preventing this kind of anomaly requires another type of guarantee: consistent prefix reads. This guarantee says that if a sequence of writes happens in a certain order, then anyone reading those writes will see them appear in the same order.

This is a particular problem in partitioned (sharded) databases. If the database always applies writes in the same order, reads always see a consistent prefix, so this anomaly cannot happen. However, in many distributed databases, different partitions operate independently, so there is no global ordering of writes: when a user reads from the database, they may see some parts of the database in an older state and some in a newer state.

One solution is to make sure that any writes that are causally related to each other are written to the same partition—but in some applications that cannot be done efficiently. There are also algorithms that explicitly keep track of causal dependencies.

Solutions for Replication Lag

As discussed earlier, there are ways in which an application can provide a stronger guarantee than the underlying database—for example, by performing certain kinds of reads on the leader. However, dealing with these issues in application code is complex and easy to get wrong.

It would be better if application developers didn’t have to worry about subtle replication issues and could just trust their databases to “do the right thing.” This is why transactions exist: they are a way for a database to provide stronger guarantees so that the application can be simpler.

Multi-Leader Replication

Leader-based replication has one major downside: there is only one leader, and all writes must go through it. If you can’t connect to the leader for any reason, you can’t write to the database. A natural extension of the leader-based replication model is to allow more than one node to accept writes. We call this a multi-leader configuration. In this setup, each leader simultaneously acts as a follower to the other leaders.

Use Cases for Multi-Leader Replication

It rarely makes sense to use a multi-leader setup within a single datacenter, because the benefits rarely outweigh the added complexity. However, there are some situations in which this configuration is reasonable.

Multi-datacenter operation

Imagine you have a database with replicas in several different datacenters (perhaps so that you can tolerate failure of an entire datacenter, or perhaps in order to be closer to your users). With a normal leader-based replication setup, the leader has to be in one of the datacenters, and all writes must go through that datacenter.

In a multi-leader configuration, you can have a leader in each datacenter. Within each datacenter, regular leader–follower replication is used; between datacenters, each datacenter’s leader replicates its changes to the leaders in other datacenters.

Although multi-leader replication has advantages, it also has a big downside: the same data may be concurrently modified in two different datacenters, and those write conflicts must be resolved.

As multi-leader replication is a somewhat retrofitted feature in many databases, there are often subtle configuration pitfalls and surprising interactions with other database features. For example, autoincrementing keys, triggers, and integrity constraints can be problematic.

Clients with offline operation

Another situation in which multi-leader replication is appropriate is if you have an application that needs to continue to work while it is disconnected from the internet.

For example, consider the calendar apps on your mobile phone, your laptop, and other devices. If you make any changes while you are offline, they need to be synced with a server and your other devices when the device is next online.

In this case, every device has a local database that acts as a leader (it accepts write requests), and there is an asynchronous multi-leader replication process (sync) between the replicas of your calendar on all of your devices. The replication lag may be hours or even days, depending on when you have internet access available.

Collaborative editing

Real-time collaborative editing applications allow several people to edit a document simultaneously. When one user edits a document, the changes are instantly applied to their local replica (the state of the document in their web browser or client application) and asynchronously replicated to the server and any other users who are editing the same document.

If you want to guarantee that there will be no editing conflicts, the application must obtain a lock on the document before a user can edit it. This collaboration model is equivalent to single-leader replication with transactions on the leader.

Handling Write Conflicts

The biggest problem with multi-leader replication is that write conflicts can occur, which means that conflict resolution is required.

Synchronous versus asynchronous conflict detection

In principle, you could make the conflict detection synchronous—i.e., wait for the write to be replicated to all replicas before telling the user that the write was successful. However, by doing so, you would lose the main advantage of multi-leader replication: allowing each replica to accept writes independently. If you want synchronous conflict detection, you might as well just use single-leader replication.

Conflict avoidance

The simplest strategy for dealing with conflicts is to avoid them: if the application can ensure that all writes for a particular record go through the same leader, then conflicts cannot occur. Since many implementations of multi-leader replication handle conflicts quite poorly, avoiding conflicts is a frequently recommended approach.

Converging toward a consistent state

There are various ways of achieving convergent conflict resolution:

-

Give each write a unique ID (e.g., a timestamp, a long random number, a UUID, or a hash of the key and value), pick the write with the highest ID as the winner, and throw away the other writes. If a timestamp is used, this technique is known as last write wins (LWW). Although this approach is popular, it is dangerously prone to data loss.

-

Give each replica a unique ID, and let writes that originated at a higher-numbered replica always take precedence over writes that originated at a lower-numbered replica. This approach also implies data loss.

-

Somehow merge the values together—e.g., order them alphabetically and then concatenate them.

-

Record the conflict in an explicit data structure that preserves all information, and write application code that resolves the conflict at some later time.

Custom conflict resolution logic

As the most appropriate way of resolving a conflict may depend on the application, most multi-leader replication tools let you write conflict resolution logic using application code. That code may be executed on write or on read:

-

On write

As soon as the database system detects a conflict in the log of replicated changes, it calls the conflict handler.

-

On read

When a conflict is detected, all the conflicting writes are stored. The next time the data is read, these multiple versions of the data are returned to the application. The application may prompt the user or automatically resolve the conflict, and write the result back to the database.

There has been some interesting research into automatically resolving conflicts caused by concurrent data modifications. A few lines of research are worth mentioning:

-

Conflict-free replicated datatypes (CRDTs) are a family of data structures for sets, maps, ordered lists, counters, etc. that can be concurrently edited by multiple users, and which automatically resolve conflicts in sensible ways.

-

Mergeable persistent data structures track history explicitly, similarly to the Git version control system, and use a three-way merge function (whereas CRDTs use two-way merges).

-

Operational transformation is the conflict resolution algorithm behind collaborative editing applications such as Etherpad and Google Docs. It was designed particularly for concurrent editing of an ordered list of items, such as the list of characters that constitute a text document.

Multi-Leader Replication Topologies

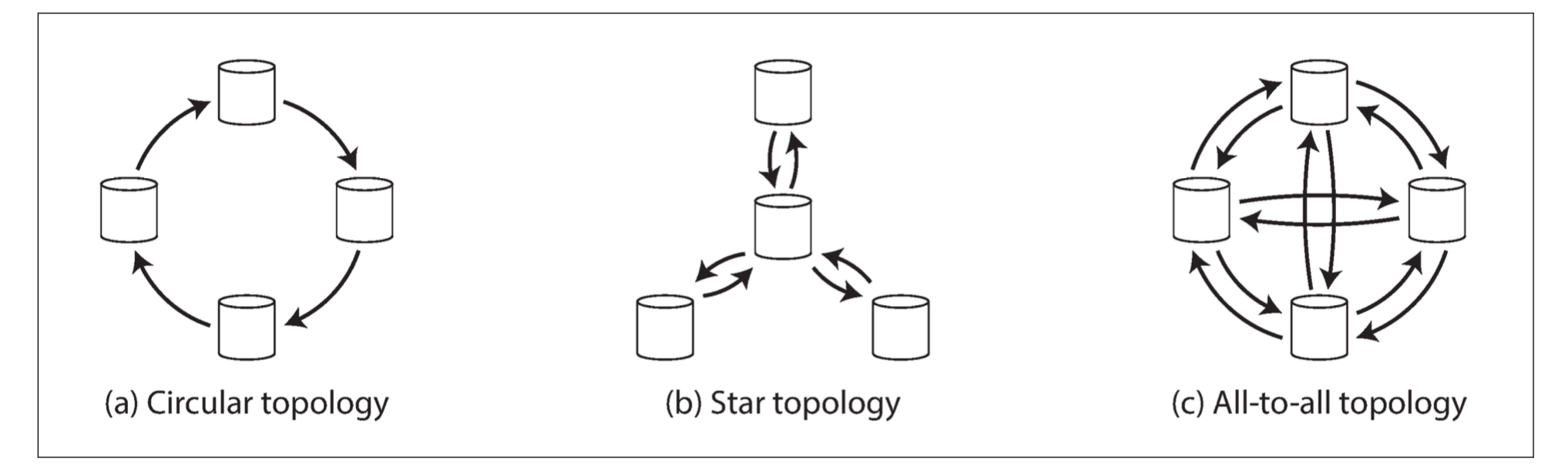

A replication topology describes the communication paths along which writes are propagated from one node to another. If you have two leaders, there is only one plausible topology: leader 1 must send all of its writes to leader 2, and vice versa. With more than two leaders, various different topologies are possible.

The most general topology is all-to-all (Figure [c]), in which every leader sends its writes to every other leader.

A problem with circular and star topologies is that if just one node fails, it can interrupt the flow of replication messages between other nodes, causing them to be unable to communicate until the node is fixed. The fault tolerance of a more densely connected topology (such as all-to-all) is better because it allows messages to travel along different paths, avoiding a single point of failure.

On the other hand, all-to-all topologies can have issues too. In particular, some network links may be faster than others (e.g., due to network congestion), with the result that some replication messages may “overtake” others.

This is a problem of causality, similar to the one we saw in “Consistent Prefix Reads”: the update depends on the prior insert, so we need to make sure that all nodes process the insert first, and then the update. Simply attaching a timestamp to every write is not sufficient, because clocks cannot be trusted to be sufficiently in sync to correctly order these events at leader 2.

To order these events correctly, a technique called version vectors can be used, which we will discuss later in this chapter. However, conflict detection techniques are poorly implemented in many multi-leader replication systems.

Leaderless Replication

In a leader-based configuration, if you want to continue processing writes, you may need to perform a failover. On the other hand, in a leaderless configuration, failover does not exist.

In some leaderless implementations, the client directly sends its writes to several replicas, while in others, a coordinator node does this on behalf of the client. However, unlike a leader database, that coordinator does not enforce a particular ordering of writes.

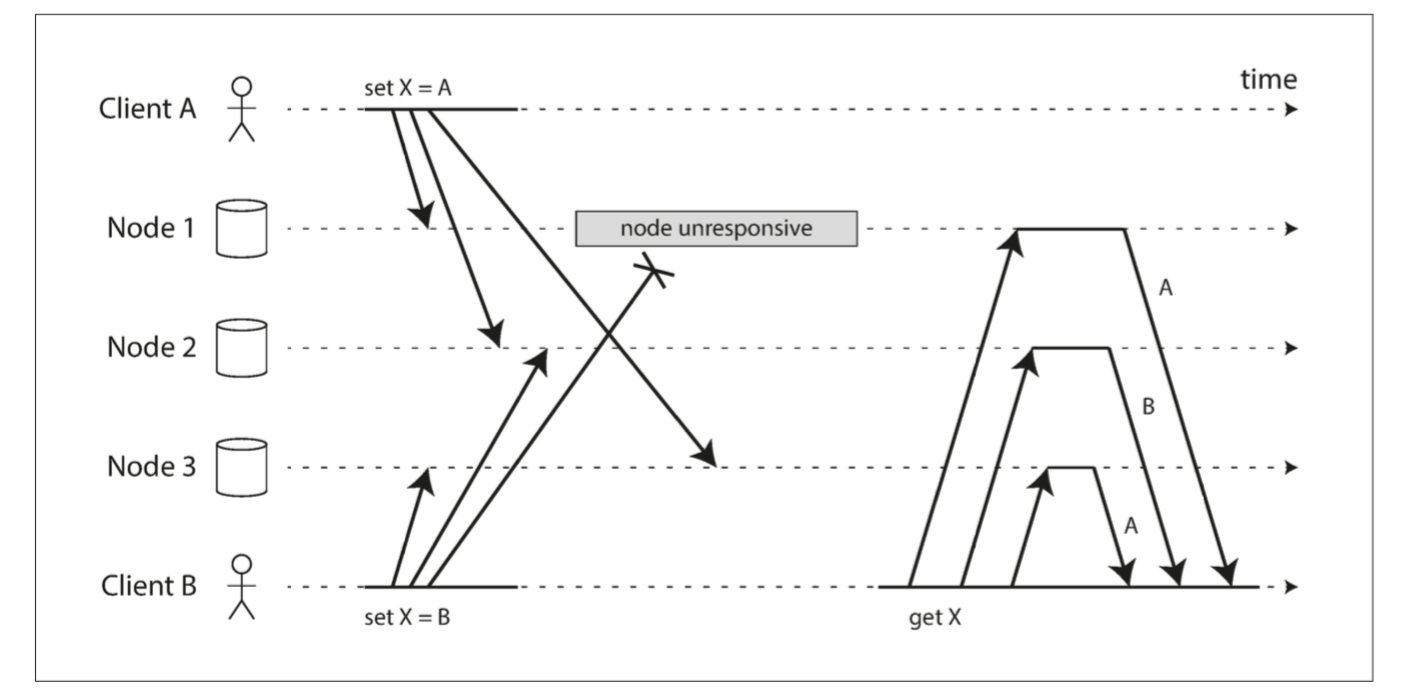

Writing to the Database When a Node Is Down

When a client reads from the database, it doesn’t just send its request to one replica: read requests are also sent to several nodes in parallel. The client may get different responses from different nodes; i.e., the up-to-date value from one node and a stale value from another. Version numbers are used to determine which value is newer.

Read repair and anti-entropy

Two mechanisms are often used in Dynamo-style datastores:

-

Read repair

When a client makes a read from several nodes in parallel, it can detect any stale responses. The client sees that replica has a stale value and writes the newer value back to that replica. This approach works well for values that are frequently read.

-

Anti-entropy process

In addition, some datastores have a background process that constantly looks for differences in the data between replicas and copies any missing data from one replica to another. Unlike the replication log in leader-based replication, this anti-entropy process does not copy writes in any particular order, and there may be a significant delay before data is copied.

Quorums for reading and writing

If there are n replicas, every write must be confirmed by w nodes to be considered successful, and we must query at least r nodes for each read. As long as w + r > n, we expect to get an up-to-date value when reading, because at least one of the r nodes we’re reading from must be up to date. Reads and writes that obey these r and w values are called quorum reads and writes.

A workload with few writes and many reads may benefit from setting w = n and r = 1. This makes reads faster, but has the disadvantage that just one failed node causes all database writes to fail.

Limitations of Quorum Consistency

However, even with w + r > n, there are likely to be edge cases where stale values are returned. These depend on the implementation, but possible scenarios include:

-

If a sloppy quorum is used, the w writes may end up on different nodes than the r reads, so there is no longer a guaranteed overlap between the r nodes and the w nodes.

-

If two writes occur concurrently, it is not clear which one happened first. In this case, the only safe solution is to merge the concurrent writes. If a winner is picked based on a timestamp (last write wins), writes can be lost due to clock skew.

-

If a write happens concurrently with a read, the write may be reflected on only some of the replicas. In this case, it’s undetermined whether the read returns the old or the new value.

-

If a node carrying a new value fails, and its data is restored from a replica carry‐ ing an old value, the number of replicas storing the new value may fall below w, breaking the quorum condition.

-

Even if everything is working correctly, there are edge cases in which you can get unlucky with the timing. See “Linearizability and quorums”

Monitoring staleness

For leader-based replication, the database typically exposes metrics for the replication lag, which you can feed into a monitoring system. By subtracting a follower’s current position from the leader’s current position, you can measure the amount of replication lag.

However, in systems with leaderless replication, there is no fixed order in which writes are applied, which makes monitoring more difficult.

Detecting Concurrent Writes

Last write wins (discarding concurrent writes)

We say the writes are concurrent, so their order is undefined. Even though the writes don’t have a natural ordering, we can force an arbitrary order on them. For example, we can attach a timestamp to each write, pick the biggest timestamp as the most “recent,” and discard any writes with an earlier timestamp. This conflict resolution algorithm, called last write wins (LWW).

LWW achieves the goal of eventual convergence, but at the cost of durability: if there are several concurrent writes to the same key, even if they were all reported as successful to the client (because they were written to w replicas), only one of the writes will survive and the others will be silently discarded. Moreover, LWW may even drop writes that are not concurrent, as we shall discuss in “Timestamps for ordering events”.

If losing data is not acceptable, LWW is a poor choice for conflict resolution. The only safe way of using a database with LWW is to ensure that a key is only written once and thereafter treated as immutable, thus avoiding any concurrent updates to the same key.

The “happens-before” relationship and concurrency

An operation A happens before another operation B if B knows about A, or depends on A, or builds upon A in some way. In fact, we can simply say that two operations are concurrent if neither happens before the other.

If one operation happened before another, the later operation should overwrite the earlier operation, but if the operations are concurrent, we have a conflict that needs to be resolved.

For defining concurrency, exact time doesn’t matter: we simply call two operations concurrent if they are both unaware of each other, regardless of the physical time at which they occurred.

Capturing the happens-before relationship

-

The server maintains a version number for every key, increments the version number every time that key is written, and stores the new version number along with the value written.

-

When a client reads a key, the server returns all values that have not been over‐ written, as well as the latest version number. A client must read a key before writing.

-

When a client writes a key, it must include the version number from the prior read, and it must merge together all values that it received in the prior read. (The response from a write request can be like a read, returning all current values, which allows us to chain several writes like in the shopping cart example.)

-

When the server receives a write with a particular version number, it can overwrite all values with that version number or below (since it knows that they have been merged into the new value), but it must keep all values with a higher version number (because those values are concurrent with the incoming write).

When a write includes the version number from a prior read, that tells us which previous state the write is based on.

Version vectors

How does the algorithm change when there are multiple replicas, but no leader?

Previous algorithm uses a single version number to capture dependencies between operations, but that is not sufficient when there are multiple replicas accepting writes concurrently. Instead, we need to use a version number per replica as well as per key. Each replica increments its own version number when processing a write, and also keeps track of the version numbers it has seen from each of the other replicas. This information indicates which values to overwrite and which values to keep as siblings.

The collection of version numbers from all the replicas is called a version vector.