Chapter 6. Partitioning

For very large datasets, or very high query throughput, that is not sufficient: we need to break the data up into partitions, also known as sharding.

The main reason for wanting to partition data is scalability. Different partitions can be placed on different nodes in a shared-nothing cluster.

In this chapter we will first look at different approaches for partitioning large datasets and observe how the indexing of data interacts with partitioning. We’ll then talk about rebalancing, which is necessary if you want to add or remove nodes in your cluster. Finally, we’ll get an overview of how databases route requests to the right partitions and execute queries.

Partitioning and Replication

Partitioning is usually combined with replication so that copies of each partition are stored on multiple nodes. Even though each record belongs to exactly one partition, it may still be stored on several different nodes for fault tolerance.

A node may store more than one partition. If a leader–follower replication model is used, the combination of partitioning and replication can look like bellow figure:

Partitioning of Key-Value Data

If the partitioning is unfair, so that some partitions have more data or queries than others, we call it skewed.

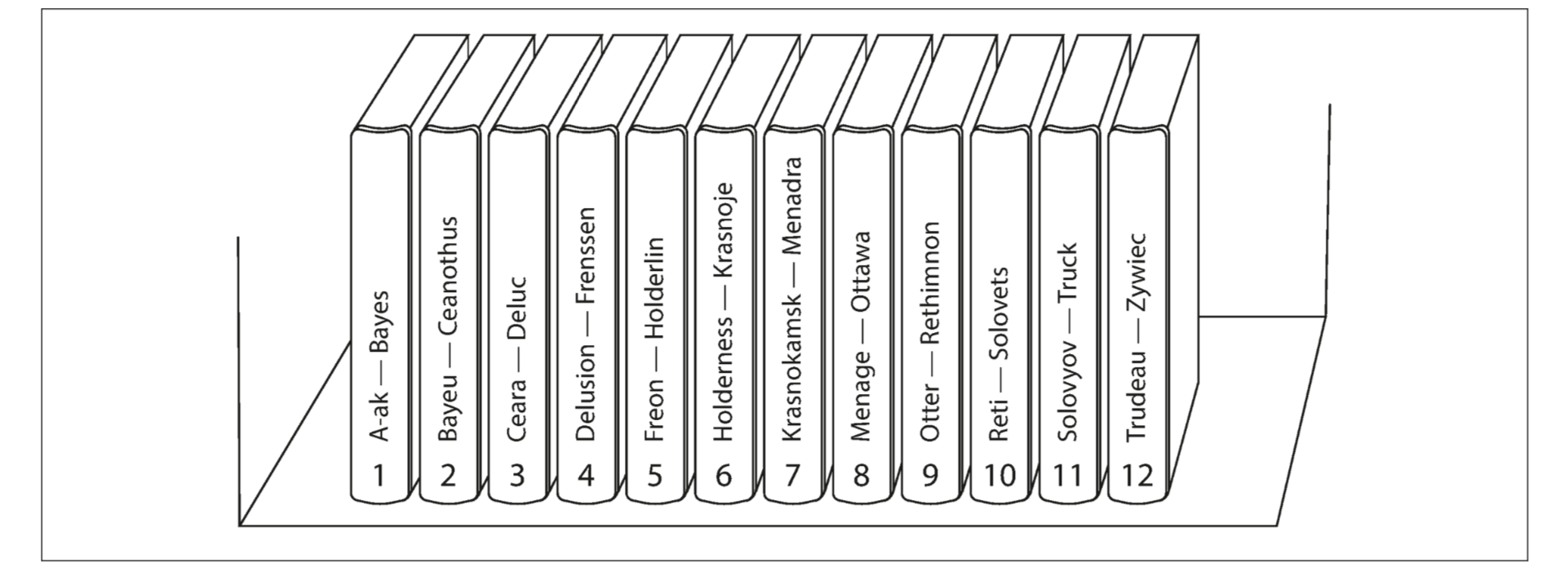

Partitioning by Key Range

Within each partition, we can keep keys in sorted order. This has the advantage that range scans are easy, and you can treat the key as a concatenated index in order to fetch several related records in one query.

Partitioning by Hash of Key

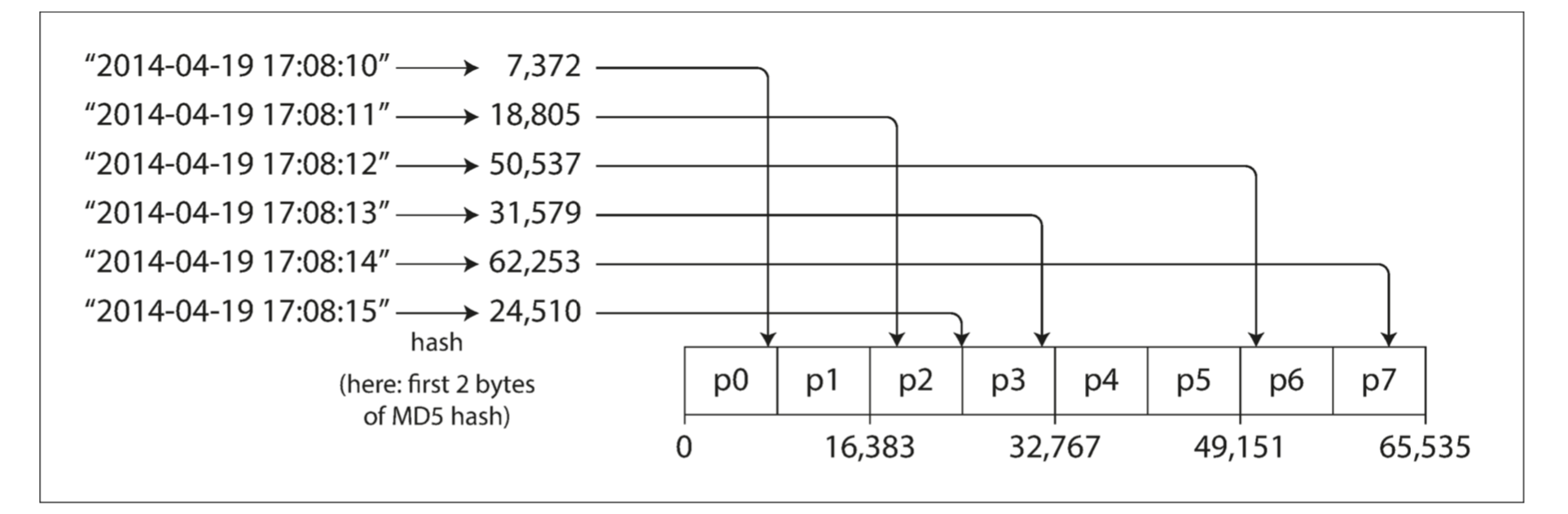

Because of this risk of skew and hot spots, many distributed datastores use a hash function to determine the partition for a given key.

Once you have a suitable hash function for keys, you can assign each partition a range of hashes (rather than a range of keys), and every key whose hash falls within a partition’s range will be stored in that partition.

Unfortunately however, by using the hash of the key for partitioning we lose a nice property of key-range partitioning: the ability to do efficient range queries. Keys that were once adjacent are now scattered across all the partitions. In MongoDB, if you have enabled hash-based sharding mode, any range query has to be sent to all partitions.

Cassandra achieves a compromise between the two partitioning strategies. A table in Cassandra can be declared with a compound primary key consisting of several columns. Only the first part of that key is hashed to determine the partition, but the other columns are used as a concatenated index for sorting the data in Cassandra’s SSTables. A query therefore cannot search for a range of values within the first column of a compound key, but if it specifies a fixed value for the first column, it can perform an efficient range scan over the other columns of the key.

Skewed Workloads and Relieving Hot Spots

As discussed, hashing a key to determine its partition can help reduce hot spots. However, it can’t avoid them entirely: in the extreme case where all reads and writes are for the same key, you still end up with all requests being routed to the same partition.

Today, most data systems are not able to automatically compensate for such a highly skewed workload, so it’s the responsibility of the application to reduce the skew. For example, if one key is known to be very hot, a simple technique is to add a random number to the beginning or end of the key. However, having split the writes across different keys, any reads now have to do additional work, as they have to read the data from all 100 keys and combine it.

Partitioning and Secondary Indexes

If records are only ever accessed via their primary key, we can determine the partition from that key and use it to route read and write requests to the partition responsible for that key.

The situation becomes more complicated if secondary indexes are involved. A secondary index usually doesn’t identify a record uniquely but rather is a way of searching for occurrences of a particular value: find all actions by user 123, find all articles containing the word hogwash, find all cars whose color is red, and so on.

The problem with secondary indexes is that they don’t map neatly to partitions. There are two main approaches to partitioning a database with secondary indexes: document-based partitioning and term-based partitioning.

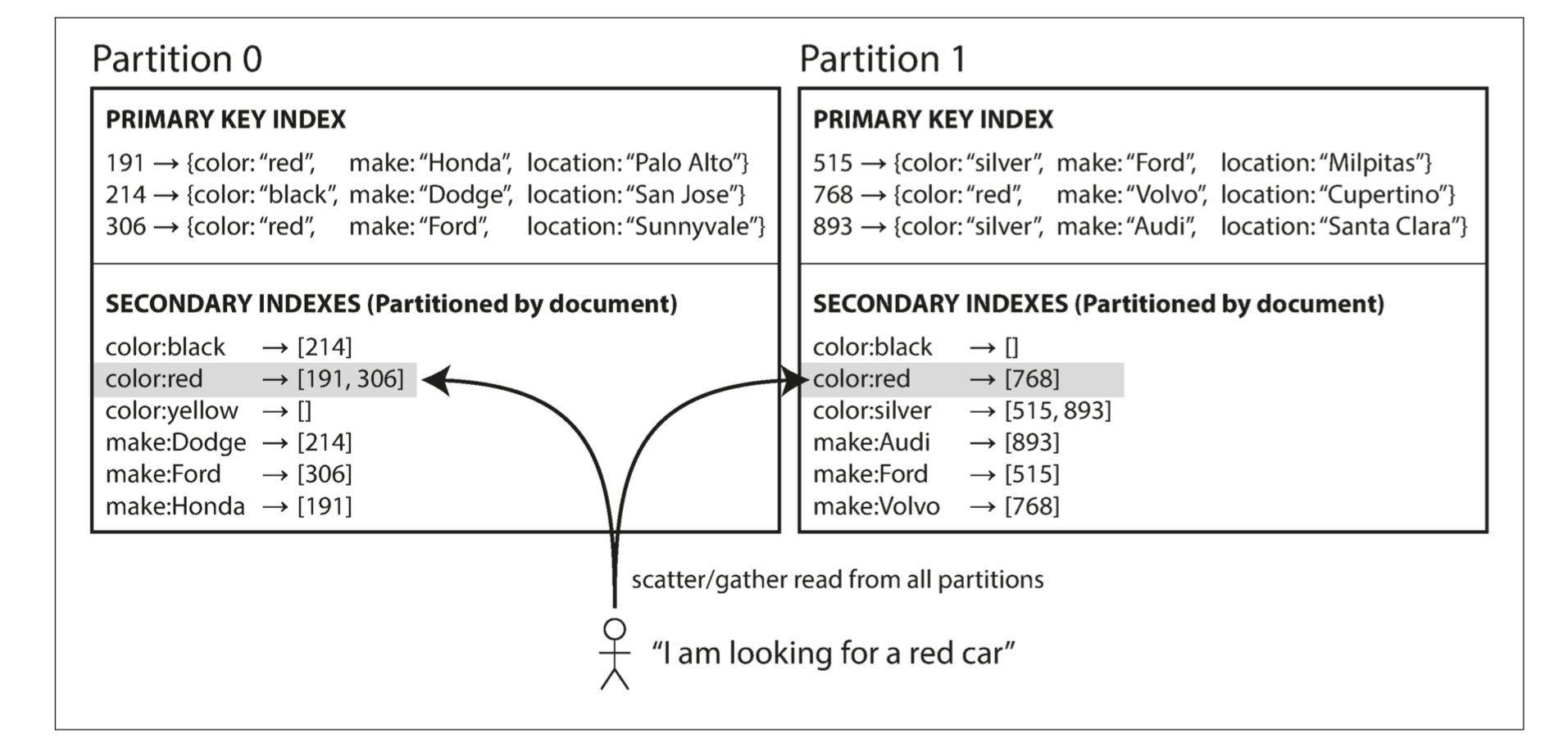

Partitioning Secondary Indexes by Document

Imagine you are operating a website for selling used cars. Each listing has a unique ID—call it the document ID—and you partition the database by the document ID.

You want to let users search for cars, allowing them to filter by color and by make, so you need a secondary index on color and make. If you have declared the index, the database can perform the indexing automatically. For example, whenever a red car is added to the database, the database partition automatically adds it to the list of document IDs for the index entry color:red.

In this indexing approach, each partition is completely separate: each partition maintains its own secondary indexes, covering only the documents in that partition. A document-partitioned index is also known as a local index (as opposed to a global index, described in the next section).

If you want to search for red cars, you need to send the query to all partitions, and combine all the results you get back.

This approach to querying a partitioned database is sometimes known as scatter/ gather, and it can make read queries on secondary indexes quite expensive. Even if you query the partitions in parallel, scatter/gather is prone to tail latency amplification(多个并行请求,请求时延由最慢的请求决定).

Partitioning Secondary Indexes by Term

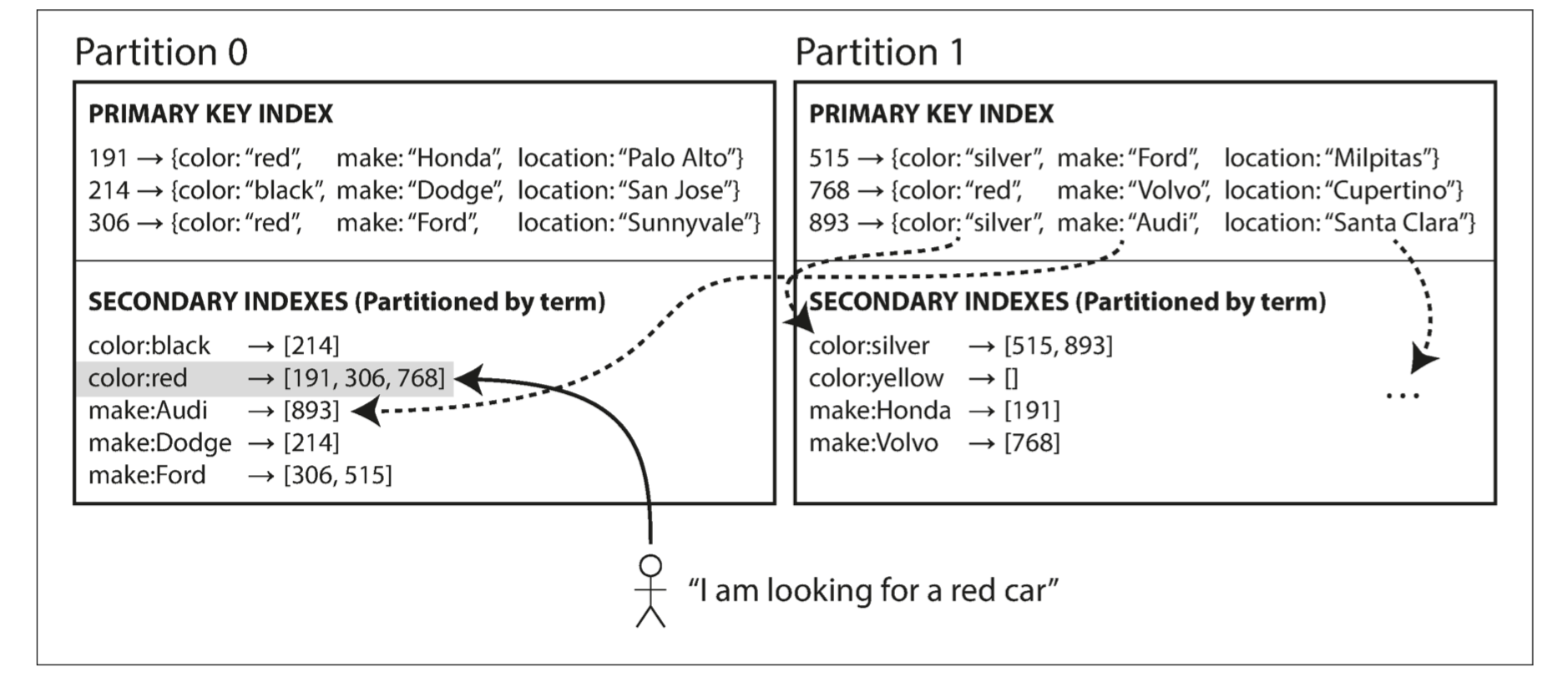

Rather than each partition having its own secondary index (a local index), we can construct a global index that covers data in all partitions. A global index must also be partitioned, but it can be partitioned differently from the primary key index.

We call this kind of index term-partitioned, because the term we’re looking for determines the partition of the index.

The advantage of a global (term-partitioned) index over a document-partitioned index is that it can make reads more efficient: rather than doing scatter/gather over all partitions, a client only needs to make a request to the partition containing the term that it wants. However, the downside of a global index is that writes are slower and more complicated, because a write to a single document may now affect multiple partitions of the index (every term in the document might be on a different partition, on a different node).

In practice, updates to global secondary indexes are often asynchronous.

Rebalancing Partitions

The process of moving load from one node in the cluster to another is called rebalancing.

No matter which partitioning scheme is used, rebalancing is usually expected to meet some minimum requirements:

- After rebalancing, the load (data storage, read and write requests) should be shared fairly between the nodes in the cluster.

- While rebalancing is happening, the database should continue accepting reads and writes.

- No more data than necessary should be moved between nodes, to make rebalancing fast and to minimize the network and disk I/O load.

Strategies for Rebalancing

How not to do it: hash mod N

The problem with the mod N approach is that if the number of nodes N changes, most of the keys will need to be moved from one node to another.

Fixed number of partitions

Fortunately, there is a fairly simple solution: create many more partitions than there are nodes, and assign several partitions to each node.

Now, if a node is added to the cluster, the new node can steal a few partitions from every existing node until partitions are fairly distributed once again.

Only entire partitions are moved between nodes. The number of partitions does not change, nor does the assignment of keys to partitions. The only thing that changes is the assignment of partitions to nodes. This change of assignment is not immediate-it takes some time to transfer a large amount of data over the network—so the old assignment of partitions is used for any reads and writes that happen while the transfer is in progress.

Choosing the right number of partitions is difficult if the total size of the dataset is highly variable.

Dynamic partitioning

key range–partitioned databases such as HBase and RethinkDB create partitions dynamically. When a partition grows to exceed a configured size, it is split into two partitions so that approximately half of the data ends up on each side of the split. Conversely, if lots of data is deleted and a partition shrinks below some threshold, it can be merged with an adjacent partition.

Partitioning proportionally to nodes

With dynamic partitioning, the number of partitions is proportional to the size of the dataset, since the splitting and merging processes keep the size of each partition between some fixed minimum and maximum. On the other hand, with a fixed number of partitions, the size of each partition is proportional to the size of the dataset. In both of these cases, the number of partitions is independent of the number of nodes.

A third option, used by Cassandra and Ketama, is to make the number of partitions proportional to the number of nodes.

When a new node joins the cluster, it randomly chooses a fixed number of existing partitions to split, and then takes ownership of one half of each of those split partitions while leaving the other half of each partition in place.

Operations: Automatic or Manual Rebalancing

Fully automated rebalancing can be convenient, however, it can be unpredictable. Rebalancing is an expensive operation, because it requires rerouting requests and moving a large amount of data from one node to another. If it is not done carefully, this process can overload the network or the nodes and harm the performance of other requests while the rebalancing is in progress.

Request Routing

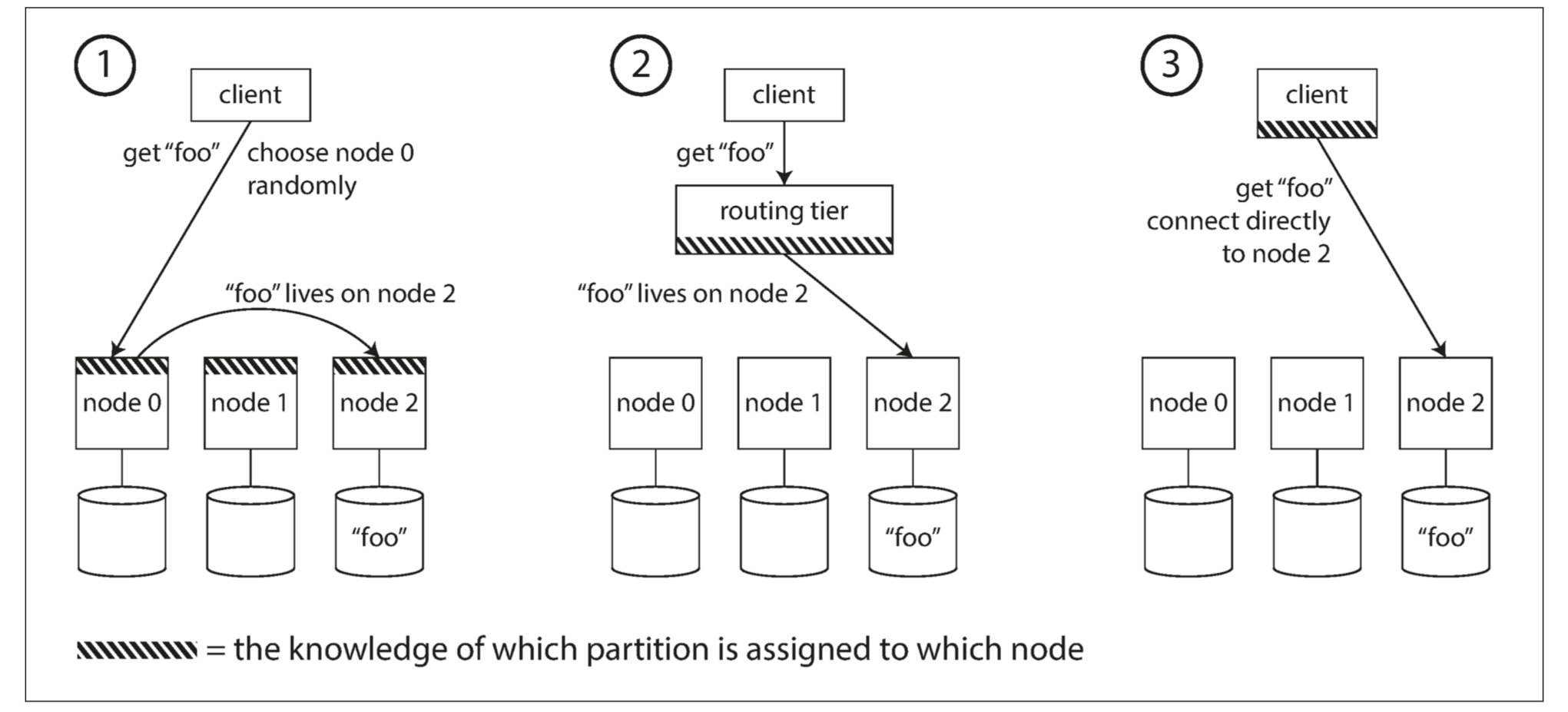

On a high level, there are a few different approaches to this problem:

-

Allow clients to contact any node (e.g., via a round-robin load balancer). If that node coincidentally owns the partition to which the request applies, it can handle the request directly; otherwise, it forwards the request to the appropriate node, receives the reply, and passes the reply along to the client.

-

Send all requests from clients to a routing tier first, which determines the node that should handle each request and forwards it accordingly. This routing tier does not itself handle any requests; it only acts as a partition-aware load balancer.

-

Require that clients be aware of the partitioning and the assignment of partitions to nodes. In this case, a client can connect directly to the appropriate node, without any intermediary.

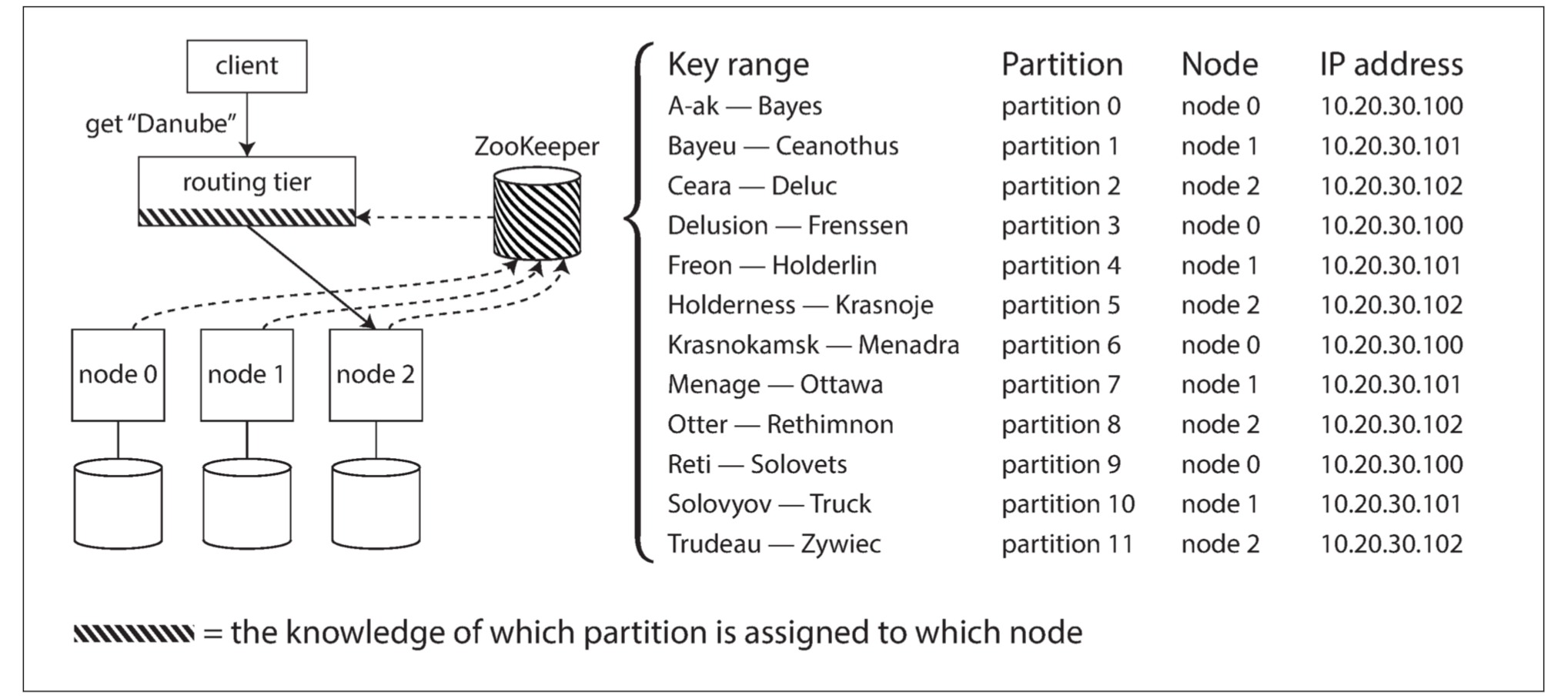

Many distributed data systems rely on a separate coordination service such as ZooKeeper to keep track of this cluster metadata:

Each node registers itself in ZooKeeper, and ZooKeeper maintains the authoritative mapping of partitions to nodes. Other actors, such as the routing tier or the partitioning-aware client, can subscribe to this information in ZooKeeper. Whenever a partition changes ownership, or a node is added or removed, ZooKeeper notifies the routing tier so that it can keep its routing information up to date.

Cassandra and Riak take a different approach: they use a gossip protocol among the nodes to disseminate any changes in cluster state. Requests can be sent to any node, and that node forwards them to the appropriate node for the requested partition.

When using a routing tier or when sending requests to a random node, clients still need to find the IP addresses to connect to. These are not as fast-changing as the assignment of partitions to nodes, so it is often sufficient to use DNS for this purpose.

Chapter 7. Transactions

A transaction is a way for an application to group several reads and writes together into a logical unit. Conceptually, all the reads and writes in a transaction are executed as one operation: either the entire transaction succeeds (commit) or it fails (abort, rollback). If it fails, the application can safely retry. With transactions, error handling becomes much simpler for an application, because it doesn’t need to worry about partial failure.

The Slippery Concept of a Transaction

The Meaning of ACID

The safety guarantees provided by transactions are often described by the well-known acronym ACID, which stands for Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability.

Atomicity

In general, atomic refers to something that cannot be broken down into smaller parts. ACID atomicity describes what happens if a client wants to make several writes, but a fault occurs after some of the writes have been processed. If the writes are grouped together into an atomic transaction, and the transaction cannot be completed (committed) due to a fault, then the transaction is aborted and the database must discard or undo any writes it has made so far in that transaction.

The ability to abort a transaction on error and have all writes from that transaction discarded is the defining feature of ACID atomicity.

Consistency

The idea of ACID consistency is that you have certain statements about your data (invariants) that must always be true–for example, in an accounting system, credits and debits across all accounts must always be balanced.

However, this idea of consistency depends on the application’s notion of invariants, and it’s the application’s responsibility to define its transactions correctly so that they preserve consistency. This is not something that the database can guarantee.

Atomicity, isolation, and durability are properties of the database, whereas consistency (in the ACID sense) is a property of the application. The application may rely on the database’s atomicity and isolation properties in order to achieve consistency, but it’s not up to the database alone. Thus, the letter C doesn’t really belong in ACID.

Isolation

Isolation in the sense of ACID means that concurrently executing transactions are isolated from each other: they cannot step on each other’s toes. The classic database textbooks formalize isolation as serializability, which means that each transaction can pretend that it is the only transaction running on the entire database. The database ensures that when the transactions have committed, the result is the same as if they had run serially (one after another), even though in reality they may have run concurrently.

However, in practice, serializable isolation is rarely used, because it carries a performance penalty.

Durability

Durability is the promise that once a transaction has committed successfully, any data it has written will not be forgotten, even if there is a hardware fault or the database crashes.

Single-Object and Multi-Object Operations

In ACID, atomicity and isolation describe what the database should do if a client makes several writes within the same transaction:

-

Atomicity If an error occurs halfway through a sequence of writes, the transaction should be aborted, and the writes made up to that point should be discarded. In other words, the database saves you from having to worry about partial failure, by giving an all-or-nothing guarantee.

-

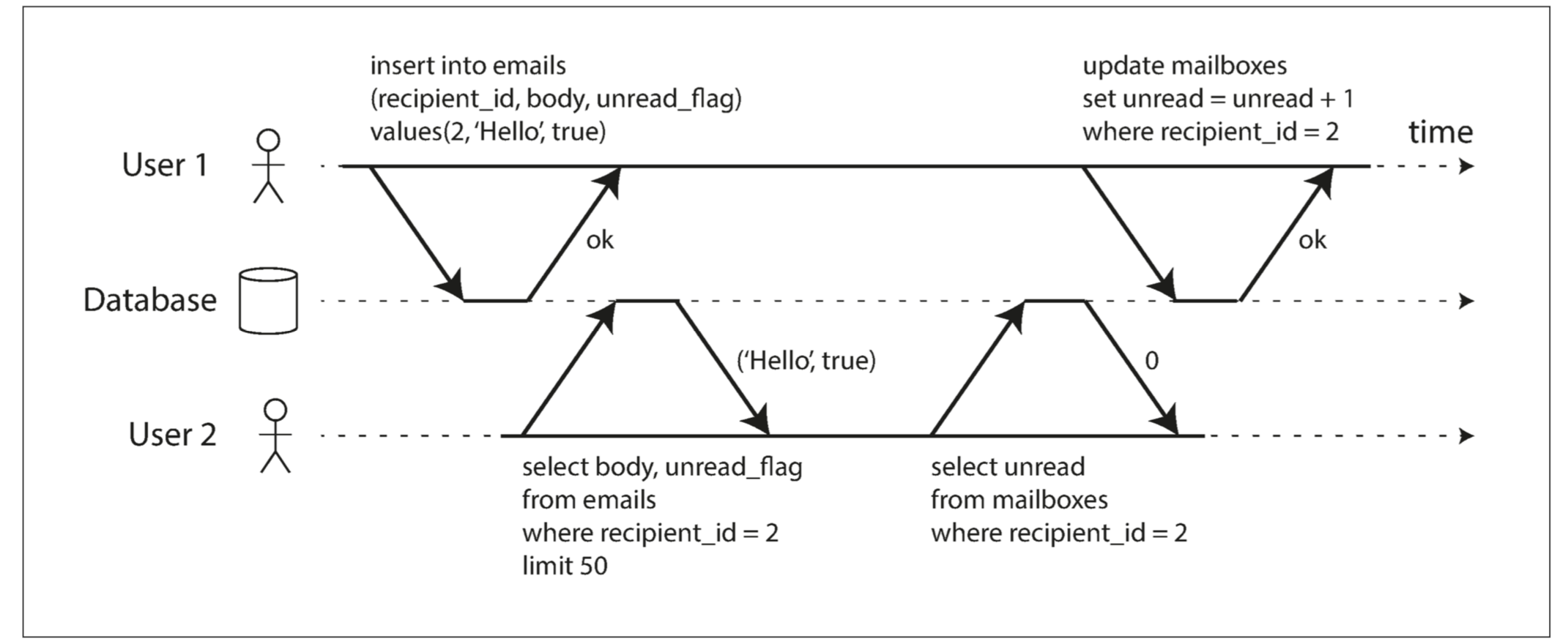

Isolation Concurrently running transactions shouldn’t interfere with each other. For example, if one transaction makes several writes, then another transaction should see either all or none of those writes, but not some subset.

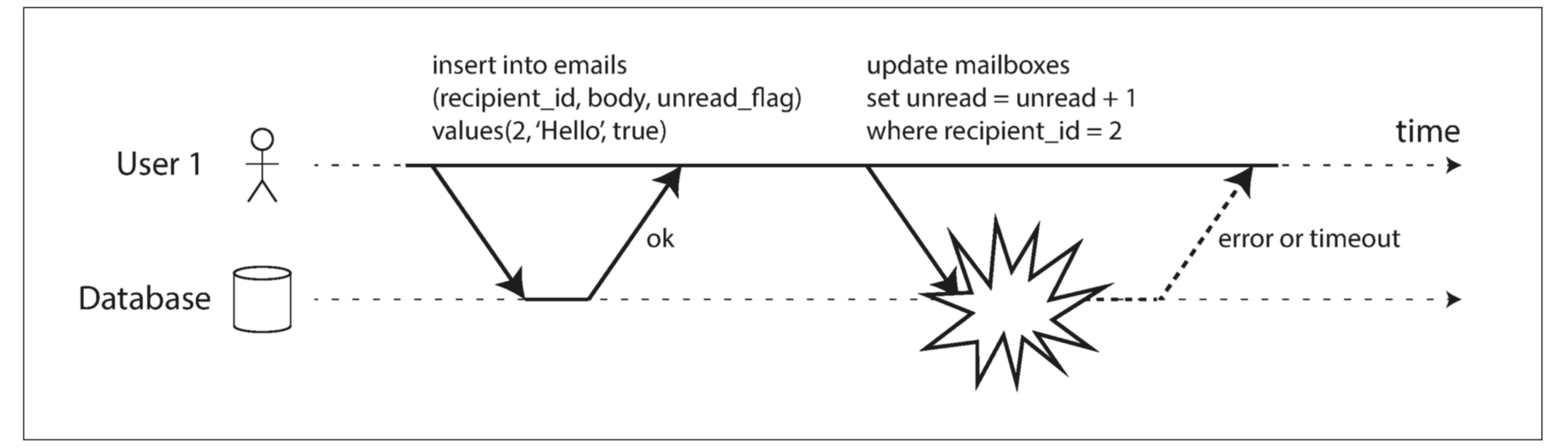

User 2 experiences an anomaly: the mailbox listing shows an unread message, but the counter shows zero unread messages because the counter increment has not yet happened.ii Isolation would have prevented this issue by ensuring that user 2 sees either both the inserted email and the updated counter, or neither, but not an inconsistent halfway point.

If an error occurs somewhere over the course of the transaction, the contents of the mailbox and the unread counter might become out of sync. In an atomic transaction, if the update to the counter fails, the transaction is aborted and the inserted email is rolled back.

Multi-object transactions require some way of determining which read and write operations belong to the same transaction. In relational databases, that is typically done based on the client’s TCP connection to the database server: on any particular connection, everything between a BEGIN TRANSACTION and a COMMIT statement is considered to be part of the same transaction.

Single-object writes

Atomicity and isolation also apply when a single object is being changed. For example, imagine you are writing a 20 KB JSON document to a database:

-

If the network connection is interrupted after the first 10 KB have been sent, does the database store that unparseable 10 KB fragment of JSON?

-

If the power fails while the database is in the middle of overwriting the previous value on disk, do you end up with the old and new values spliced together?

-

If another client reads that document while the write is in progress, will it see a partially updated value?

Atomicity can be implemented using a log for crash recovery and isolation can be implemented using a lock on each object (allowing only one thread to access an object at any one time).

Some databases also provide more complex atomic operations, such as an increment operation, which removes the need for a read-modify-write cycle. Similarly popular is a compare-and-set operation, which allows a write to happen only if the value has not been concurrently changed by someone else.

These single-object operations are useful, as they can prevent lost updates when several clients try to write to the same object concurrently.

Handling errors and aborts

ACID databases are based on this philosophy: if the database is in danger of violating its guarantee of atomicity, isolation, or durability, it would rather abandon the transaction entirely than allow it to remain half-finished.

Not all systems follow that philosophy, though. In particular, datastores with leaderless replication work much more on a “best effort” basis, which could be summarized as “the database will do as much as it can, and if it runs into an error, it won’t undo something it has already done”—so it’s the application’s responsibility to recover from errors.

Although retrying an aborted transaction is a simple and effective error handling mechanism, it isn’t perfect:

-

If the transaction actually succeeded, but the network failed while the server tried to acknowledge the successful commit to the client (so the client thinks it failed), then retrying the transaction causes it to be performed twice—unless you have an additional application-level deduplication mechanism in place.

-

If the error is due to overload, retrying the transaction will make the problem worse, not better. To avoid such feedback cycles, you can limit the number of retries, use exponential backoff, and handle overload-related errors differently from other errors (if possible).

-

It is only worth retrying after transient errors (for example due to deadlock, isolation violation, temporary network interruptions, and failover); after a permanent error (e.g., constraint violation) a retry would be pointless.

-

If the transaction also has side effects outside of the database, those side effects may happen even if the transaction is aborted. For example, if you’re sending an email, you wouldn’t want to send the email again every time you retry the transaction. If you want to make sure that several different systems either commit or abort together, two-phase commit can help.

-

If the client process fails while retrying, any data it was trying to write to the database is lost.

Weak Isolation Levels

Databases have long tried to hide concurrency issues from application developers by providing transaction isolation. Serializable isolation means that the database guarantees that transactions have the same effect as if they ran serially.

Serializable isolation has a performance cost, and many databases don’t want to pay that price. It’s therefore common for systems to use weaker levels of isolation, which protect against some concurrency issues, but not all.

Read Committed

The most basic level of transaction isolation is read committed. It makes two guarantees:

- When reading from the database, you will only see data that has been committed (no dirty reads).

- When writing to the database, you will only overwrite data that has been committed (no dirty writes).

No dirty reads

Imagine a transaction has written some data to the database, but the transaction has not yet committed or aborted. Can another transaction see that uncommitted data? If yes, that is called a dirty read.

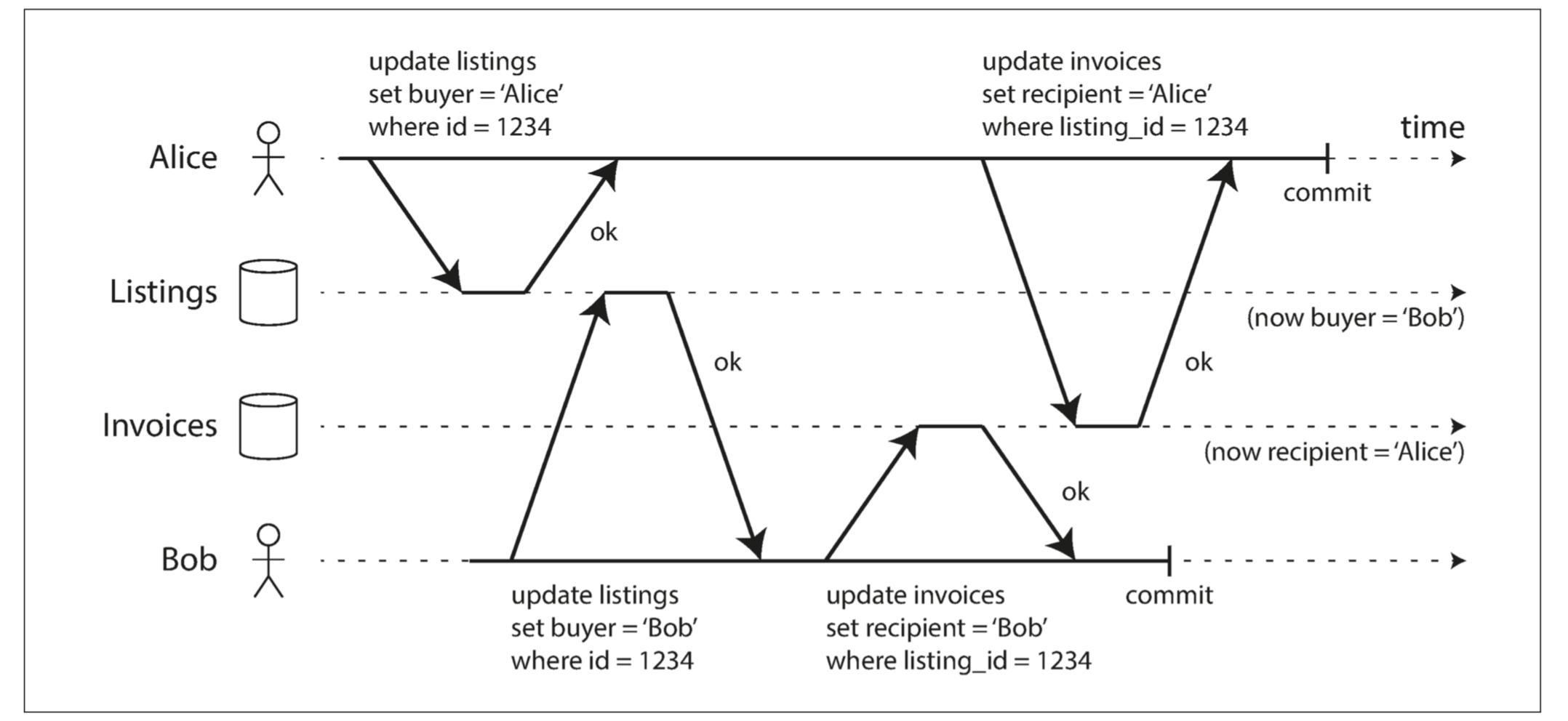

No dirty writes

If the earlier write is part of a transaction that has not yet committed, so the later write overwrites an uncommitted value? This is called a dirty write.

Transactions running at the read committed isolation level must prevent dirty writes, usually by delaying the second write until the first write’s transaction has committed or aborted.

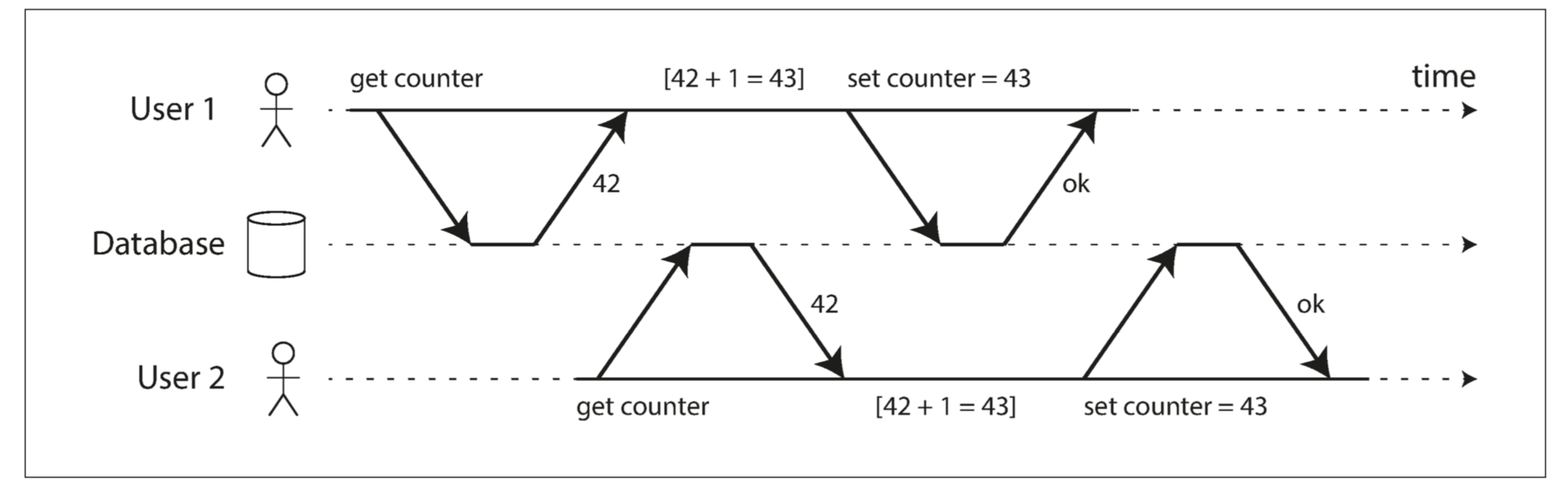

However, read committed does not prevent the race condition between two counter increments.

Implementing read committed

Most commonly, databases prevent dirty writes by using row-level locks: when a transaction wants to modify a particular object (row or document), it must first acquire a lock on that object. It must then hold that lock until the transaction is committed or aborted.

How do we prevent dirty reads? One option would be to use the same lock, and to require any transaction that wants to read an object to briefly acquire the lock and then release it again immediately after reading. This would ensure that a read couldn’t happen while an object has a dirty, uncommitted value.

However, the approach of requiring read locks does not work well in practice, because one long-running write transaction can force many read-only transactions to wait until the long-running transaction has completed.

For that reason, most databasesvi prevent dirty reads using the following approach: for every object that is written, the database remembers both the old committed value and the new value set by the transaction that currently holds the write lock. While the transaction is ongoing, any other transactions that read the object are simply given the old value. Only when the new value is committed do transactions switch over to reading the new value.

Snapshot Isolation and Repeatable Read

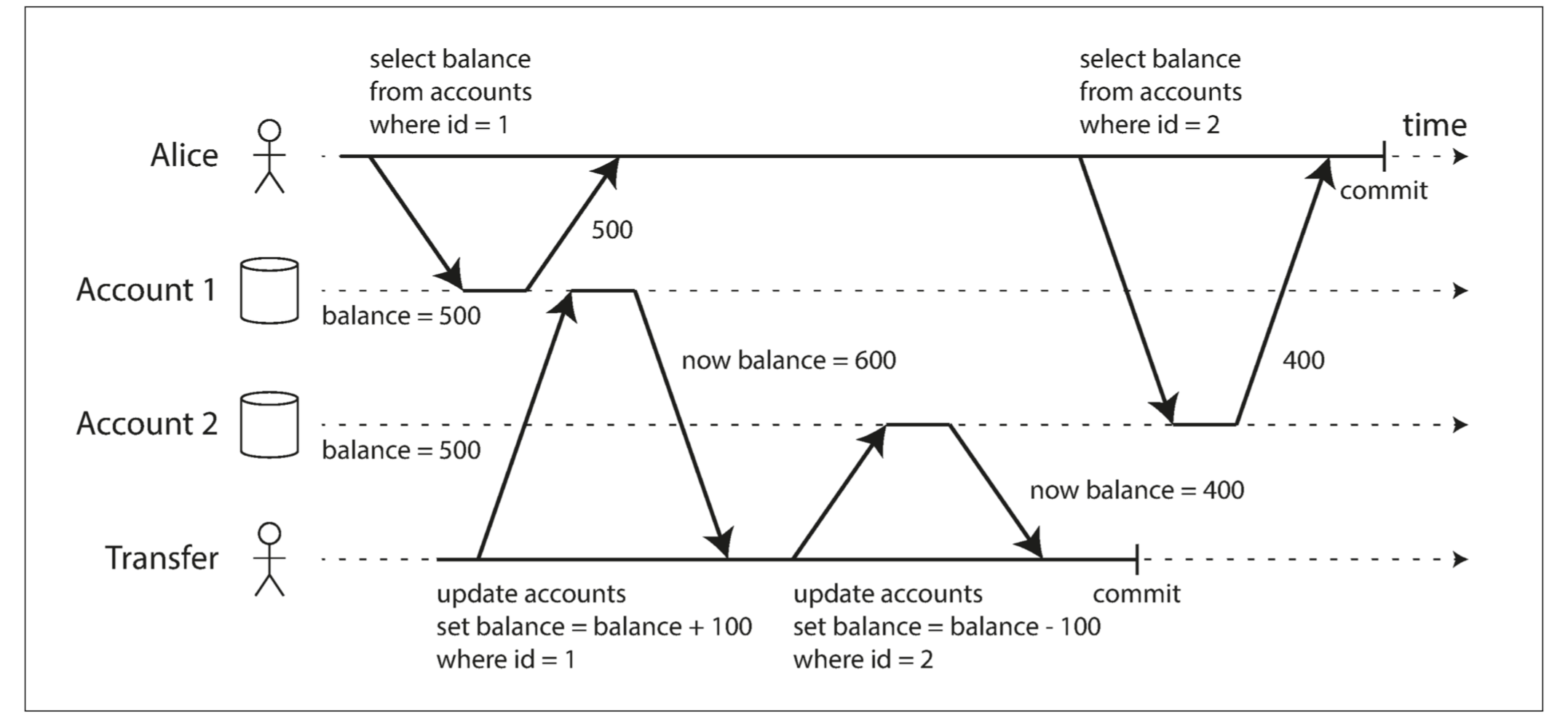

Figure below illustrates a problem that can occur with read committed.

This anomaly is called a nonrepeatable read or read skew.

Some situations cannot tolerate such temporary inconsistency:

-

Backups

Taking a backup requires making a copy of the entire database, which may take hours on a large database. During the time that the backup process is running, writes will continue to be made to the database. Thus, you could end up with some parts of the backup containing an older version of the data, and other parts containing a newer version. If you need to restore from such a backup, the inconsistencies (such as disappearing money) become permanent.

-

Analytic queries and integrity checks

Sometimes, you may want to run a query that scans over large parts of the database. Such queries are common in analytics, or may be part of a periodic integrity check that everything is in order (monitoring for data corruption). These queries are likely to return nonsensical results if they observe parts of the database at different points in time.

Snapshot isolation is the most common solution to this problem. The idea is that each transaction reads from a consistent snapshot of the database—that is, the transaction sees all the data that was committed in the database at the start of the transaction. Even if the data is subsequently changed by another transaction, each transaction sees only the old data from that particular point in time.

Implementing snapshot isolation

Like read committed isolation, implementations of snapshot isolation typically use write locks to prevent dirty writes, which means that a transaction that makes a write can block the progress of another transaction that writes to the same object. However, reads do not require any locks. From a performance point of view, a key principle of snapshot isolation is readers never block writers, and writers never block readers.

The database must potentially keep several different committed versions of an object, because various in-progress transactions may need to see the state of the database at different points in time. Because it maintains several versions of an object side by side, this technique is known as multi-version concurrency control (MVCC).

If a database only needed to provide read committed isolation, but not snapshot isolation, it would be sufficient to keep two versions of an object: the committed version and the overwritten-but-not-yet-committed version. However, storage engines that support snapshot isolation typically use MVCC for their read committed isolation level as well.

Following figure illustrates how MVCC-based snapshot isolation is implemented in PostgreSQL(other implementations are similar). When a transaction is started, it is given a unique, always-increasing transaction ID (txid). Whenever a transaction writes anything to the database, the data it writes is tagged with the transaction ID of the writer.

Each row in a table has a created_by field, containing the ID of the transaction that inserted this row into the table. Moreover, each row has a deleted_by field, which is initially empty. If a transaction deletes a row, the row isn’t actually deleted from the database, but it is marked for deletion by setting the deleted_by field to the ID of the transaction that requested the deletion. At some later time, when it is certain that no transaction can any longer access the deleted data, a garbage collection process in the database removes any rows marked for deletion and frees their space.

Visibility rules for observing a consistent snapshot

By carefully defining visibility rules, the database can present a consistent snapshot of the database to the application. This works as follows:

-

At the start of each transaction, the database makes a list of all the other transactions that are in progress (not yet committed or aborted) at that time. Any writes that those transactions have made are ignored, even if the transactions subsequently commit.

-

Any writes made by aborted transactions are ignored.

-

Any writes made by transactions with a later transaction ID (i.e., which started after the current transaction started) are ignored, regardless of whether those transactions have committed.

-

All other writes are visible to the application’s queries.

Put another way, an object is visible if both of the following conditions are true:

-

At the time when the reader’s transaction started, the transaction that created the object had already committed.

-

The object is not marked for deletion, or if it is, the transaction that requested deletion had not yet committed at the time when the reader’s transaction started.

By never updating values in place but instead creating a new version every time a value is changed, the database can provide a consistent snapshot while incurring only a small overhead.

Indexes and snapshot isolation

How do indexes work in a multi-version database? One option is to have the index simply point to all versions of an object and require an index query to filter out any object versions that are not visible to the current transaction.

PostgreSQL has optimizations for avoiding index updates if different versions of the same object can fit on the same page.

Another approach is used in CouchDB, Datomic, and LMDB. Although they also use B-trees, they use an append-only/copy-on-write variant that does not overwrite pages of the tree when they are updated, but instead creates a new copy of each modified page. Parent pages, up to the root of the tree, are copied and updated to point to the new versions of their child pages. Any pages that are not affected by a write do not need to be copied, and remain immutable.

With append-only B-trees, every write transaction (or batch of transactions) creates a new B-tree root, and a particular root is a consistent snapshot of the database at the point in time when it was created. There is no need to filter out objects based on transaction IDs because subsequent writes cannot modify an existing B-tree; they can only create new tree roots. However, this approach also requires a background process for compaction and garbage collection.

Repeatable read and naming confusion

Snapshot isolation is a useful isolation level, especially for read-only transactions. However, many databases that implement it call it by different names. In Oracle it is called serializable, and in PostgreSQL and MySQL it is called repeatable read.

Preventing Lost Updates

The lost update problem can occur if an application reads some value from the database, modifies it, and writes back the modified value (a read-modify-write cycle). If two transactions do this concurrently, one of the modifications can be lost, because the second write does not include the first modification.

Atomic write operations

Many databases provide atomic update operations, which remove the need to implement read-modify-write cycles in application code.

Atomic operations are usually implemented by taking an exclusive lock on the object when it is read so that no other transaction can read it until the update has been applied. This technique is sometimes known as cursor stability. Another option is to simply force all atomic operations to be executed on a single thread.

Explicit locking

Another option for preventing lost updates, is for the application to explicitly lock objects that are going to be updated.

Automatically detecting lost updates

An alternative is to allow them to execute in parallel and, if the transaction manager detects a lost update, abort the transaction and force it to retry its read-modify-write cycle.

An advantage of this approach is that databases can perform this check efficiently in conjunction with snapshot isolation.

Compare-and-set

The purpose of this operation is to avoid lost updates by allowing an update to happen only if the value has not changed since you last read it.

However, if the database allows the WHERE clause to read from an old snapshot, this statement may not prevent lost updates, because the condition may be true even though another concurrent write is occurring. Check whether your database’s compare-and-set operation is safe before relying on it.(如果读的是old snapshot 则不安全)

Conflict resolution and replication

In replicated databases, preventing lost updates takes on another dimension: since they have copies of the data on multiple nodes, and the data can potentially be modified concurrently on different nodes, some additional steps need to be taken to prevent lost updates.

That is the idea behind Riak 2.0 datatypes, which prevent lost updates across replicas. When a value is concurrently updated by different clients, Riak automatically merges together the updates in such a way that no updates are lost.

On the other hand, the last write wins (LWW) conflict resolution method is prone to lost updates, as discussed in “Last write wins (discarding concurrent writes)”. Unfortunately, LWW is the default in many replicated databases.

Write Skew and Phantoms

More examples of write skew

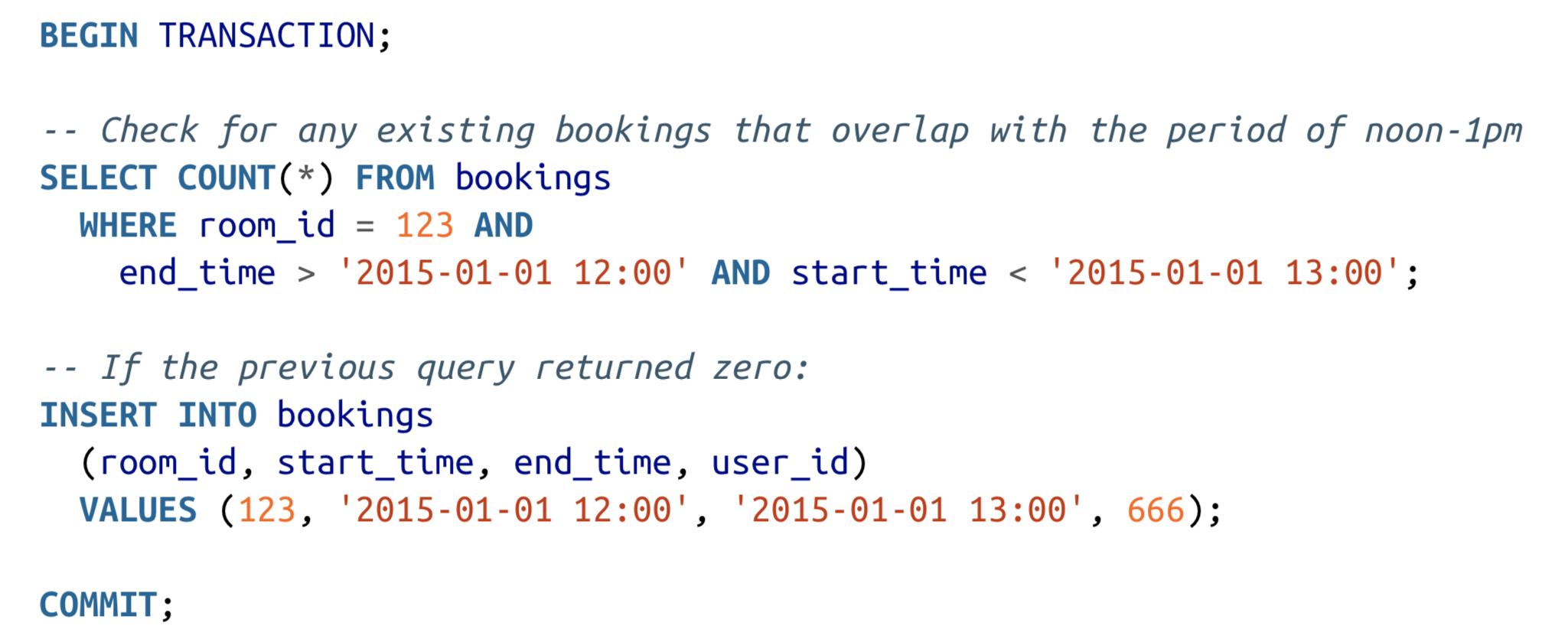

Unfortunately, snapshot isolation does not prevent another user from concurrently inserting a conflicting meeting. In order to guarantee you won’t get scheduling conflicts, you once again need serializable isolation.

Characterizing write skew

This anomaly is called write skew. It is neither a dirty write nor a lost update, because the two transactions are updating two different objects.

With write skew, our options are more restricted:

-

Atomic single-object operations don’t help, as multiple objects are involved.

-

The automatic detection of lost updates that you find in some implementations of snapshot isolation unfortunately doesn’t help either: write skew is not automatically detected in PostgreSQL’s repeatable read, MySQL/InnoDB’s repeatable read, Oracle’s serializable, or SQL Server’s snapshot isolation level. Auto‐matically preventing write skew requires true serializable isolation.

-

In order to specify that at least one doctor must be on call, you would need a constraint that involves multiple objects. Most databases do not have built-in support for such constraints, but you may be able to implement them with triggers or materialized views, depending on the database.

-

If you can’t use a serializable isolation level, the second-best option in this case is probably to explicitly lock the rows that the transaction depends on.

Phantoms causing write skew

All of these examples follow a similar pattern:

-

A SELECT query checks whether some requirement is satisfied by searching for rows that match some search condition (there are at least two doctors on call, there are no existing bookings for that room at that time, the position on the board doesn’t already have another figure on it, the username isn’t already taken, there is still money in the account).

-

Depending on the result of the first query, the application code decides how to continue (perhaps to go ahead with the operation, or perhaps to report an error to the user and abort).

-

If the application decides to go ahead, it makes a write (INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE) to the database and commits the transaction.

In the case of the doctor on call example, the row being modified in step 3 was one of the rows returned in step 1, so we could make the transaction safe and avoid write skew by locking the rows in step 1 (SELECT FOR UPDATE). However, the other four examples are different: they check for the absence of rows matching some search condition, and the write adds a row matching the same condition. If the query in step 1 doesn’t return any rows, SELECT FOR UPDATE can’t attach locks to anything.

This effect, where a write in one transaction changes the result of a search query in another transaction, is called a phantom. Snapshot isolation avoids phantoms in read-only queries, but in read-write transactions like the examples we discussed, phantoms can lead to particularly tricky cases of write skew.

Materializing conflicts

If the problem of phantoms is that there is no object to which we can attach the locks, perhaps we can artificially introduce a lock object into the database?

For example, in the meeting room booking case you could imagine creating a table of time slots and rooms. Each row in this table corresponds to a particular room for a particular time period. Now a transaction that wants to create a booking can lock (SELECT FOR UPDATE) the rows in the table that correspond to the desired room and time period. After it has acquired the locks, it can check for overlapping bookings and insert a new booking as before.

This approach is called materializing conflicts, because it takes a phantom and turns it into a lock conflict on a concrete set of rows that exist in the database. Unfortunately, it can be hard and error-prone to figure out how to materialize conflicts, and it’s ugly to let a concurrency control mechanism leak into the application data model. For those reasons, materializing conflicts should be considered a last resort if no alternative is possible. A serializable isolation level is much preferable in most cases.

Serializability

It’s a sad situation:

-

Isolation levels are hard to understand, and inconsistently implemented in different databases.

-

If you look at your application code, it’s difficult to tell whether it is safe to run at a particular isolation level.

-

There are no good tools to help us detect race conditions.

Serializable isolation is usually regarded as the strongest isolation level. It guarantees that even though transactions may execute in parallel, the end result is the same as if they had executed one at a time, serially, without any concurrency.

Most databases that provide serializability today use one of three techniques:

-

Literally executing transactions in a serial order

-

Two-phase locking, which for several decades was the only viable option

-

Optimistic concurrency control techniques such as serializable snapshot isolation

Actual Serial Execution

The simplest way of avoiding concurrency problems is to remove the concurrency entirely: to execute only one transaction at a time, in serial order, on a single thread.

The approach of executing transactions serially is implemented in VoltDB/H-Store, Redis, and Datomic. A system designed for single-threaded execution can sometimes perform better than a system that supports concurrency, because it can avoid the coordination overhead of locking. However, its throughput is limited to that of a single CPU core.

Encapsulating transactions in stored procedures

In this interactive style of transaction, a lot of time is spent in network communication between the application and the database. If you were to disallow concurrency in the database and only process one transaction at a time, the throughput would be dreadful because the database would spend most of its time waiting for the applica‐ tion to issue the next query for the current transaction.

For this reason, systems with single-threaded serial transaction processing don’t allow interactive multi-statement transactions. Instead, the application must submit the entire transaction code to the database ahead of time, as a stored procedure.

Partitioning

If you can find a way of partitioning your dataset so that each transaction only needs to read and write data within a single partition, then each partition can have its own transaction processing thread running independently from the others.

However, for any transaction that needs to access multiple partitions, the database must coordinate the transaction across all the partitions that it touches. The stored procedure needs to be performed in lock-step across all partitions to ensure serializability across the whole system.

Whether transactions can be single-partition depends very much on the structure of the data used by the application. Simple key-value data can often be partitioned very easily, but data with multiple secondary indexes is likely to require a lot of cross-partition coordination.

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

Several transactions are allowed to concurrently read the same object as long as nobody is writing to it. But as soon as anyone wants to write (modify or delete) an object, exclusive access is required:

-

If transaction A has read an object and transaction B wants to write to that object, B must wait until A commits or aborts before it can continue. (This ensures that B can’t change the object unexpectedly behind A’s back.)

-

If transaction A has written an object and transaction B wants to read that object, B must wait until A commits or aborts before it can continue. (Reading an old version of the object, is not acceptable under 2PL.)

In 2PL, writers don’t just block other writers; they also block readers and vice versa. Snapshot isolation has the mantra readers never block writers, and writers never block readers, which captures this key difference between snapshot isolation and two-phase locking.

On the other hand, because 2PL provides serializability, it protects against all the race conditions discussed earlier, including lost updates and write skew.

Implementation of two-phase locking

2PL is used by the serializable isolation level in MySQL (InnoDB) and SQL Server, and the repeatable read isolation level in DB2.

The blocking of readers and writers is implemented by a having a lock on each object in the database. The lock can either be in shared mode or in exclusive mode. The lock is used as follows:

-

If a transaction wants to read an object, it must first acquire the lock in shared mode. Several transactions are allowed to hold the lock in shared mode simultaneously, but if another transaction already has an exclusive lock on the object, these transactions must wait.

-

If a transaction wants to write to an object, it must first acquire the lock in exclusive mode. No other transaction may hold the lock at the same time (either in shared or in exclusive mode), so if there is any existing lock on the object, the transaction must wait.

-

If a transaction first reads and then writes an object, it may upgrade its shared lock to an exclusive lock. The upgrade works the same as getting an exclusive lock directly.

-

After a transaction has acquired the lock, it must continue to hold the lock until the end of the transaction (commit or abort). This is where the name “two-phase” comes from: the first phase (while the transaction is executing) is when the locks are acquired, and the second phase (at the end of the transaction) is when all the locks are released.

Since so many locks are in use, it can happen quite easily that transaction A is stuck waiting for transaction B to release its lock, and vice versa. This situation is called deadlock. The database automatically detects deadlocks between transactions and aborts one of them so that the others can make progress. The aborted transaction needs to be retried by the application.

Performance of two-phase locking

The big downside of two-phase locking, and the reason why it hasn’t been used by everybody since the 1970s, is performance: transaction throughput and response times of queries are significantly worse under two-phase locking than under weak isolation.

Predicate locks

We discussed the problem of phantoms—that is, one transaction changing the results of another transaction’s search query. A database with serializable isolation must prevent phantoms.

In the meeting room booking example this means that if one transaction has searched for existing bookings for a room within a certain time window, another transaction is not allowed to concurrently insert or update another booking for the same room and time range.

How do we implement this? Conceptually, we need a predicate lock.

A predicate lock restricts access as follows:

-

If transaction A wants to read objects matching some condition, like in that SELECT query, it must acquire a shared-mode predicate lock on the conditions of the query. If another transaction B currently has an exclusive lock on any object matching those conditions, A must wait until B releases its lock before it is allowed to make its query.

-

If transaction A wants to insert, update, or delete any object, it must first check whether either the old or the new value matches any existing predicate lock. If there is a matching predicate lock held by transaction B, then A must wait until B has committed or aborted before it can continue.

If two-phase locking includes predicate locks, the database prevents all forms of write skew and other race conditions, and so its isolation becomes serializable.

Index-range locks

Unfortunately, predicate locks do not perform well: if there are many locks by active transactions, checking for matching locks becomes time-consuming. For that reason, most databases with 2PL actually implement index-range locking(also known as next-key locking), which is a simplified approximation of predicate locking.

It’s safe to simplify a predicate by making it match a greater set of objects. For example, if you have a predicate lock for bookings of room 123 between noon and 1 p.m., you can approximate it by locking bookings for room 123 at any time, or you can approximate it by locking all rooms (not just room 123) between noon and 1 p.m.

In the room bookings database you would probably have an index on the room_id column, and/or indexes on start_time and end_time:

-

Say your index is on room_id, and the database uses this index to find existing bookings for room 123. Now the database can simply attach a shared lock to this index entry, indicating that a transaction has searched for bookings of room 123.

-

Alternatively, if the database uses a time-based index to find existing bookings, it can attach a shared lock to a range of values in that index, indicating that a transaction has searched for bookings that overlap with the time period of noon to 1 p.m. on January 1, 2018.

Either way, an approximation of the search condition is attached to one of the indexes. Now, if another transaction wants to insert, update, or delete a booking for the same room and/or an overlapping time period, it will have to update the same part of the index. In the process of doing so, it will encounter the shared lock, and it will be forced to wait until the lock is released.

Index-range locks are not as precise as predicate locks would be (they may lock a bigger range of objects than is strictly necessary to maintain serializability), but since they have much lower overheads, they are a good compromise.

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

An algorithm called serializable snapshot isolation (SSI) is very promising. It provides full serializability, but has only a small performance penalty compared to snapshot isolation.

As SSI is so young compared to other concurrency control mechanisms, it is still proving its performance in practice, but it has the possibility of being fast enough to become the new default in the future.

Pessimistic versus optimistic concurrency control

Two-phase locking is a so-called pessimistic concurrency control mechanism: it is based on the principle that if anything might possibly go wrong (as indicated by a lock held by another transaction), it’s better to wait until the situation is safe again before doing anything. It is like mutual exclusion, which is used to protect data structures in multi-threaded programming.

By contrast, serializable snapshot isolation is an optimistic concurrency control technique. Optimistic in this context means that instead of blocking if something potentially dangerous happens, transactions continue anyway, in the hope that everything will turn out all right.

When a transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether anything bad happened (i.e., whether isolation was violated); if so, the transaction is aborted and has to be retried. Only transactions that executed serializably are allowed to commit.

As the name suggests, SSI is based on snapshot isolation—that is, all reads within a transaction are made from a consistent snapshot of the database. On top of snapshot isolation, SSI adds an algorithm for detecting serialization conflicts among writes and determining which transactions to abort.

Decisions based on an outdated premise

Under snapshot isolation, the result from the original query may no longer be up-to-date by the time the transaction commits, because the data may have been modified in the meantime.

Put another way, the transaction is taking an action based on a premise (a fact that was true at the beginning of the transaction, e.g., “There are currently two doctors on call”). Later, when the transaction wants to commit, the original data may have changed—the premise may no longer be true.

How does the database know if a query result might have changed? There are two cases to consider:

- Detecting reads of a stale MVCC object version (uncommitted write occurred before the read)

- Detecting writes that affect prior reads (the write occurs after the read)

Detecting stale MVCC reads

In Figure, transaction 43 sees Alice as having on_call = true, because transaction 42 (which modified Alice’s on-call status) is uncommitted. However, by the time transaction 43 wants to commit, transaction 42 has already committed. This means that the write that was ignored when reading from the consistent snapshot has now taken effect, and transaction 43’s premise is no longer true.

In order to prevent this anomaly, the database needs to track when a transaction ignores another transaction’s writes due to MVCC visibility rules. When the transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether any of the ignored writes have now been committed. If so, the transaction must be aborted.

Why wait until committing? Why not abort transaction 43 immediately when the stale read is detected? Well, if transaction 43 was a read-only transaction, it wouldn’t need to be aborted, because there is no risk of write skew. At the time when transaction 43 makes its read, the database doesn’t yet know whether that transaction is going to later perform a write. Moreover, transaction 42 may yet abort or may still be uncommitted at the time when transaction 43 is committed, and so the read may turn out not to have been stale after all. By avoiding unnecessary aborts, SSI preserves snapshot isolation’s support for long-running reads from a consistent snapshot.

Detecting writes that affect prior reads

The second case to consider is when another transaction modifies data after it has been read.

Transactions 42 and 43 both search for on-call doctors during shift 1234. If there is an index on shift_id, the database can use the index entry 1234 to record the fact that transactions 42 and 43 read this data.

When a transaction writes to the database, it must look in the indexes for any other transactions that have recently read the affected data. This process is similar to acquiring a write lock on the affected key range, but rather than blocking until the readers have committed, the lock acts as a tripwire: it simply notifies the transactions that the data they read may no longer be up to date.

Performance of serializable snapshot isolation

Compared to two-phase locking, the big advantage of serializable snapshot isolation is that one transaction doesn’t need to block waiting for locks held by another transaction. Like under snapshot isolation, writers don’t block readers, and vice versa.

Compared to serial execution, serializable snapshot isolation is not limited to the throughput of a single CPU core.

The rate of aborts significantly affects the overall performance of SSI. However, SSI is probably less sensitive to slow transactions than two-phase locking or serial execution.

Summary

Transactions are an abstraction layer that allows an application to pretend that certain concurrency problems and certain kinds of hardware and software faults don’t exist. A large class of errors is reduced down to a simple transaction abort, and the application just needs to try again.

In this chapter, we went particularly deep into the topic of concurrency control. We discussed several widely used isolation levels, in particular read committed, snapshot isolation (sometimes called repeatable read), and serializable.

-

Dirty reads

One client reads another client’s writes before they have been committed. The read committed isolation level and stronger levels prevent dirty reads.

-

Dirty writes

One client overwrites data that another client has written, but not yet committed. Almost all transaction implementations prevent dirty writes.

-

Read skew (nonrepeatable reads)

A client sees different parts of the database at different points in time. This issue is most commonly prevented with snapshot isolation, which allows a transaction to read from a consistent snapshot at one point in time. It is usually implemented with multi-version concurrency control (MVCC).

-

Lost updates

Two clients concurrently perform a read-modify-write cycle. One overwrites the other’s write without incorporating its changes, so data is lost. Some implementations of snapshot isolation prevent this anomaly automatically, while others require a manual lock (SELECT FOR UPDATE).

-

Write skew

A transaction reads something, makes a decision based on the value it saw, and writes the decision to the database. However, by the time the write is made, the premise of the decision is no longer true. Only serializable isolation prevents this anomaly.

-

Phantom reads

A transaction reads objects that match some search condition. Another client makes a write that affects the results of that search. Snapshot isolation prevents straightforward phantom reads, but phantoms in the context of write skew require special treatment, such as index-range locks.

Only serializable isolation protects against all of these issues. We discussed three different approaches to implementing serializable transactions:

-

Literally executing transactions in a serial order

If you can make each transaction very fast to execute, and the transaction throughput is low enough to process on a single CPU core

-

Two-phase locking

For decades this has been the standard way of implementing serializability, but many applications avoid using it because of its performance characteristics.

-

Serializable snapshot isolation (SSI)

A fairly new algorithm that avoids most of the downsides of the previous approaches. It uses an optimistic approach, allowing transactions to proceed without blocking. When a transaction wants to commit, it is checked, and it is aborted if the execution was not serializable.