Chapter 8. The Trouble with Distributed Systems

Faults and Partial Failures

In a distributed system, there may well be some parts of the system that are broken in some unpredictable way, even though other parts of the system are working fine. This is known as a partial failure. The difficulty is that partial failures are nondeterministic: if you try to do anything involving multiple nodes and the network, it may sometimes work and sometimes unpredictably fail. As we shall see, you may not even know whether something succeeded or not, as the time it takes for a message to travel across a network is also nondeterministic!

Cloud Computing and Supercomputing

There is a spectrum of philosophies on how to build large-scale computing systems:

-

At one end of the scale is the field of high-performance computing (HPC). Super‐computers with thousands of CPUs are typically used for computationally intensive scientific computing tasks, such as weather forecasting or molecular dynamics (simulating the movement of atoms and molecules).

-

At the other extreme is cloud computing, which is not very well defined but is often associated with multi-tenant datacenters, commodity computers connected with an IP network (often Ethernet), elastic/on-demand resource allocation, and metered billing.

-

Traditional enterprise datacenters lie somewhere between these extremes.

With these philosophies come very different approaches to handling faults. In a supercomputer, a job typically checkpoints the state of its computation to durable storage from time to time. If one node fails, a common solution is to simply stop the entire cluster workload. After the faulty node is repaired, the computation is restarted from the last checkpoint. Thus, a supercomputer is more like a single-node computer than a distributed system: it deals with partial failure by letting it escalate into total failure—if any part of the system fails, just let everything crash (like a kernel panic on a single machine).

If we want to make distributed systems work, we must accept the possibility of partial failure and build fault-tolerance mechanisms into the software. In other words, we need to build a reliable system from unreliable components.

Unreliable Networks

The internet and most internal networks in datacenters (often Ethernet) are asynchronous packet networks. In this kind of network, one node can send a message (a packet) to another node, but the network gives no guarantees as to when it will arrive, or whether it will arrive at all.

The usual way of handling this issue is a timeout: after some time you give up waiting and assume that the response is not going to arrive. However, when a timeout occurs, you still don’t know whether the remote node got your request or not.

Detecting Faults

Many systems need to automatically detect faulty nodes. For example:

-

A load balancer needs to stop sending requests to a node that is dead (i.e., take it out of rotation).

-

In a distributed database with single-leader replication, if the leader fails, one of the followers needs to be promoted to be the new leader.

Rapid feedback about a remote node being down is useful, but you can’t count on it. Even if TCP acknowledges that a packet was delivered, the application may have crashed before handling it. If you want to be sure that a request was successful, you need a positive response from the application itself.

Conversely, if something has gone wrong, you may get an error response at some level of the stack, but in general you have to assume that you will get no response at all. You can retry a few times (TCP retries transparently, but you may also retry at the application level), wait for a timeout to elapse, and eventually declare the node dead if you don’t hear back within the timeout.

Timeouts and Unbounded Delays

When a node is declared dead, its responsibilities need to be transferred to other nodes, which places additional load on other nodes and the network. If the system is already struggling with high load, declaring nodes dead prematurely can make the problem worse.

Imagine a fictitious system with a network that guaranteed a maximum delay for packets—every packet is either delivered within some time d, or it is lost, but delivery never takes longer than d. Furthermore, assume that you can guarantee that a non-failed node always handles a request within some time r. In this case, you could guarantee that every successful request receives a response within time 2d + r—and if you don’t receive a response within that time, you know that either the network or the remote node is not working. If this was true, 2d + r would be a reasonable timeout to use.

Unfortunately, most systems we work with have neither of those guarantees: asynchronous networks have unbounded delays, and most server implementations cannot guarantee that they can handle requests within some maximum time.

Synchronous Versus Asynchronous Networks

Can we not simply make network delays predictable?

Note that a circuit in a telephone network is very different from a TCP connection: a circuit is a fixed amount of reserved bandwidth which nobody else can use while the circuit is established, whereas the packets of a TCP connection opportunistically use whatever network bandwidth is available.

If datacenter networks and the internet were circuit-switched networks, it would be possible to establish a guaranteed maximum round-trip time when a circuit was set up. However, they are not: Ethernet and IP are packet-switched protocols, which suffer from queueing and thus unbounded delays in the network. These protocols do not have the concept of a circuit.

Why do datacenter networks and the internet use packet switching? The answer is that they are optimized for bursty traffic. A circuit is good for an audio or video call, which needs to transfer a fairly constant number of bits per second for the duration of the call. On the other hand, requesting a web page, sending an email, or transferring a file doesn’t have any particular bandwidth requirement—we just want it to complete as quickly as possible.

Unreliable Clocks

Each machine on the network has its own clock, which is an actual hardware device: usually a quartz crystal oscillator. These devices are not perfectly accurate, so each machine has its own notion of time, which may be slightly faster or slower than on other machines. It is possible to synchronize clocks to some degree: the most commonly used mechanism is the Network Time Protocol (NTP), which allows the computer clock to be adjusted according to the time reported by a group of servers.

Monotonic Versus Time-of-Day Clocks

Modern computers have at least two different kinds of clocks: a time-of-day clock and a monotonic clock.

Time-of-day clocks

A time-of-day clock does what you intuitively expect of a clock: it returns the current date and time according to some calendar (also known as wall-clock time).

Time-of-day clocks are usually synchronized with NTP, which means that a timestamp from one machine (ideally) means the same as a timestamp on another machine.

If the local clock is too far ahead of the NTP server, it may be forcibly reset and appear to jump back to a previous point in time. These jumps, as well as the fact that they often ignore leap seconds, make time-of-day clocks unsuitable for measuring elapsed time.

Monotonic clocks

A monotonic clock is suitable for measuring a duration (time interval), such as a timeout or a service’s response time: clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC) on Linux and System.nanoTime() in Java are monotonic clocks.

In a distributed system, using a monotonic clock for measuring elapsed time (e.g., timeouts) is usually fine, because it doesn’t assume any synchronization between different nodes’ clocks and is not sensitive to slight inaccuracies of measurement.

Relying on Synchronized Clocks

If you use software that requires synchronized clocks, it is essential that you also carefully monitor the clock offsets between all the machines. Any node whose clock drifts too far from the others should be declared dead and removed from the cluster. Such monitoring ensures that you notice the broken clocks before they can cause too much damage.

Timestamps for ordering events

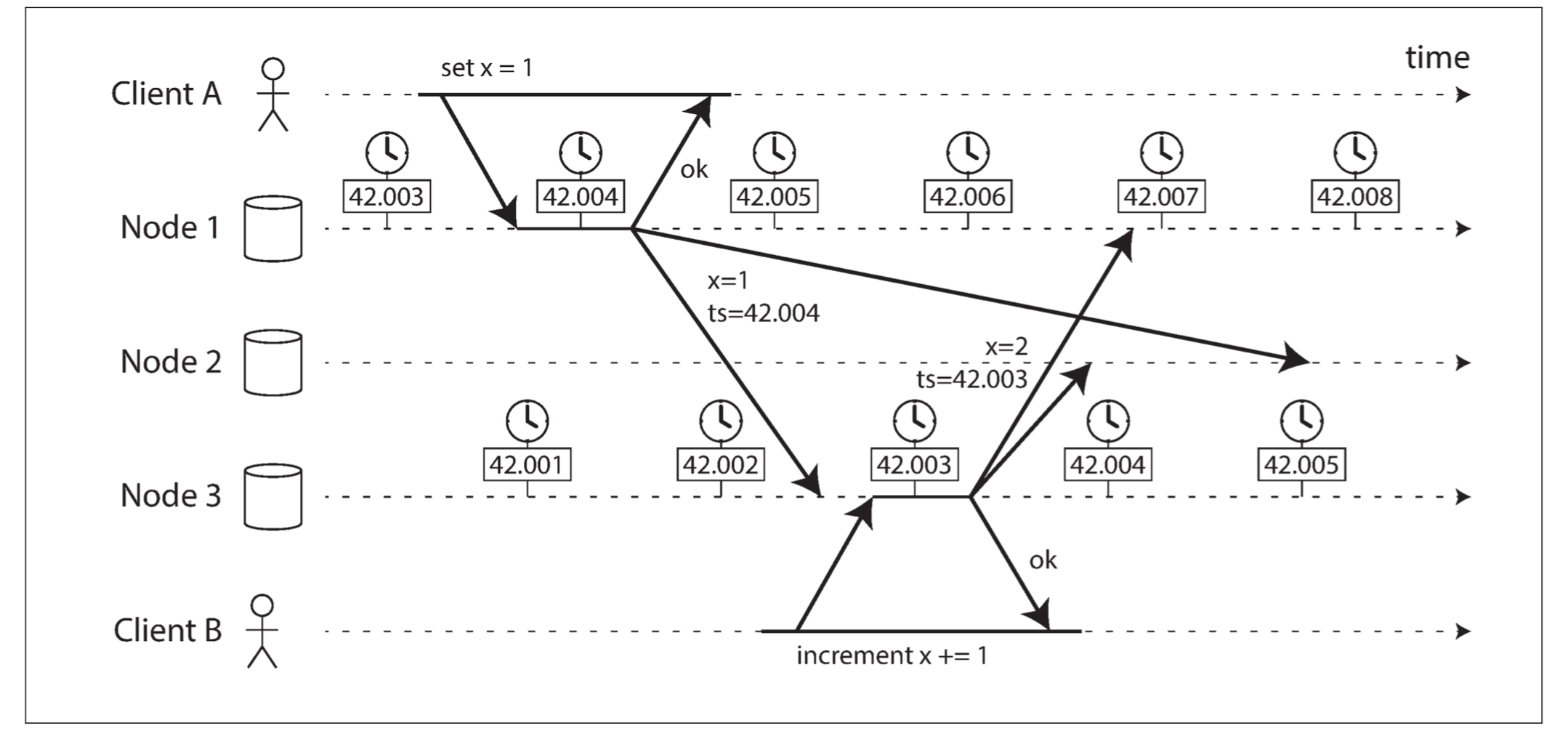

Figure illustrates a dangerous use of time-of-day clocks in a database with multi-leader replication:

The write x = 1 has a timestamp of 42.004 seconds, but the write x = 2 has a timestamp of 42.003 seconds, even though x = 2 occurred unambiguously later. When node 2 receives these two events, it will incorrectly conclude that x = 1 is the more recent value and drop the write x = 2. In effect, client B’s increment operation will be lost.

This conflict resolution strategy is called last write wins (LWW), and it is widely used in both multi-leader replication and leaderless databases such as Cassandra and Riak.

Some implementations generate timestamps on the client rather than the server, but this doesn’t change the fundamental problems with LWW:

-

Database writes can mysteriously disappear: a node with a lagging clock is unable to overwrite values previously written by a node with a fast clock until the clock skew between the nodes has elapsed. This scenario can cause arbitrary amounts of data to be silently dropped without any error being reported to the application.

-

LWW cannot distinguish between writes that occurred sequentially in quick succession and writes that were truly concurrent (neither writer was aware of the other). Additional causality tracking mechanisms, such as version vectors, are needed in order to prevent violations of causality.

-

It is possible for two nodes to independently generate writes with the same timestamp, especially when the clock only has millisecond resolution. An additional tiebreaker value (which can simply be a large random number) is required to resolve such conflicts, but this approach can also lead to violations of causality.

Thus, even though it is tempting to resolve conflicts by keeping the most “recent” value and discarding others, it’s important to be aware that the definition of “recent” depends on a local time-of-day clock, which may well be incorrect. Even with tightly NTP-synchronized clocks, you could send a packet at timestamp 100 ms (according to the sender’s clock) and have it arrive at timestamp 99 ms (according to the recipient’s clock)—so it appears as though the packet arrived before it was sent, which is impossible.

So-called logical clocks, which are based on incrementing counters rather than an oscillating quartz crystal, are a safer alternative for ordering events.

Clock readings have a confidence interval

With an NTP server on the public internet, the best possible accuracy is probably to the tens of milliseconds, and the error may easily spike to over 100 ms when there is network congestion. Thus, it doesn’t make sense to think of a clock reading as a point in time—it is more like a range of times, within a confidence interval.

Google’s TrueTime API in Spanner which explicitly reports the confidence interval on the local clock. When you ask it for the current time, you get back two values: [earliest, latest], which are the earliest possible and the latest possible timestamp. Based on its uncertainty calculations, the clock knows that the actual current time is somewhere within that interval.

Synchronized clocks for global snapshots

The most common implementation of snapshot isolation requires a monotonically increasing transaction ID. If a write happened later than the snapshot (i.e., the write has a greater transaction ID than the snapshot), that write is invisible to the snapshot transaction. On a single-node database, a simple counter is sufficient for generating transaction IDs.

However, when a database is distributed across many machines, potentially in multiple datacenters, a global, monotonically increasing transaction ID (across all partitions) is difficult to generate, because it requires coordination. With lots of small, rapid transactions, creating transaction IDs in a distributed system becomes an untenable bottleneck.

Spanner implements snapshot isolation across datacenters in this way: it uses the clock’s confidence interval as reported by the TrueTime API.

In order to ensure that transaction timestamps reflect causality, Spanner deliberately waits for the length of the confidence interval before committing a read-write transaction. By doing so, it ensures that any transaction that may read the data is at a sufficiently later time, so their confidence intervals do not overlap.

Process Pauses

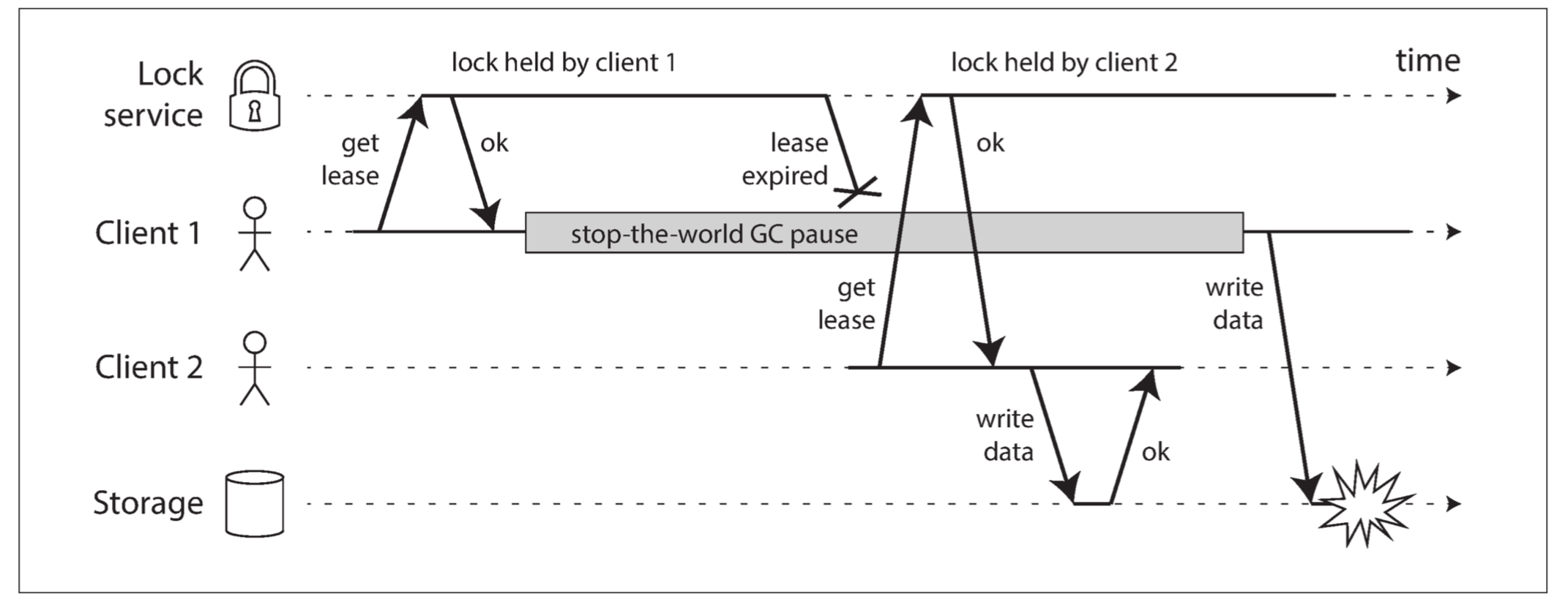

Let’s consider another example of dangerous clock use in a distributed system. Say you have a database with a single leader per partition. Only the leader is allowed to accept writes. How does a node know that it is still leader, and that it may safely accept writes?

Only the leader is allowed to accept writes. Only one node can hold the lease at any one time—thus, when a node obtains a lease, it knows that it is the leader for some amount of time, until the lease expires.

You can imagine the request-handling loop looking something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

while (true) {

request = getIncomingRequest();

// Ensure that the lease always has at least 10 seconds remaining

if (lease.expiryTimeMillis - System.currentTimeMillis() < 10000) {

lease = lease.renew();

}

if (lease.isValid()) {

process(request);

}

}

What’s wrong with this code? Firstly, it’s relying on synchronized clocks: the expiry time on the lease is set by a different machine, and it’s being compared to the local system clock. If the clocks are out of sync by more than a few seconds, this code will start doing strange things.

Secondly, even if we change the protocol to only use the local monotonic clock, there is another problem: the code assumes that very little time passes between the point that it checks the time (System.currentTimeMillis()) and the time when the request is processed (process(request)). Normally this code runs very quickly, so the 10 second buffer is more than enough to ensure that the lease doesn’t expire in the middle of processing a request.

However, what if there is an unexpected pause in the execution of the program? For example, imagine the thread stops for 15 seconds around the line lease.isValid() before finally continuing. In that case, it’s likely that the lease will have expired by the time the request is processed, and another node has already taken over as leader.

Is it crazy to assume that a thread might be paused for so long? Unfortunately not. There are various reasons why this could happen:

-

Many programming language runtimes (such as the Java Virtual Machine) have a garbage collector (GC) that occasionally needs to stop all running threads. These “stop-the-world” GC pauses have sometimes been known to last for several minutes!

-

In virtualized environments, a virtual machine can be suspended (pausing the execution of all processes and saving the contents of memory to disk) and resumed (restoring the contents of memory and continuing execution). This pause can occur at any time in a process’s execution and can last for an arbitrary length of time. This feature is sometimes used for live migration of virtual machines from one host to another without a reboot, in which case the length of the pause depends on the rate at which processes are writing to memory.

-

On end-user devices such as laptops, execution may also be suspended and resumed arbitrarily, e.g., when the user closes the lid of their laptop.

-

When the operating system context-switches to another thread, or when the hypervisor switches to a different virtual machine (when running in a virtual machine), the currently running thread can be paused at any arbitrary point in the code. In the case of a virtual machine, the CPU time spent in other virtual machines is known as steal time. If the machine is under heavy load—i.e., if there is a long queue of threads waiting to run—it may take some time before the paused thread gets to run again.

-

If the application performs synchronous disk access, a thread may be paused waiting for a slow disk I/O operation to complete.

-

If the operating system is configured to allow swapping to disk (paging), a simple memory access may result in a page fault that requires a page from disk to be loaded into memory. The thread is paused while this slow I/O operation takes place. If memory pressure is high, this may in turn require a different page to be swapped out to disk. In extreme circumstances, the operating system may spend most of its time swapping pages in and out of memory and getting little actual work done (this is known as thrashing). To avoid this problem, paging is often disabled on server machines.

-

A Unix process can be paused by sending it the SIGSTOP signal, for example by pressing Ctrl-Z in a shell. This signal immediately stops the process from getting any more CPU cycles until it is resumed with SIGCONT, at which point it contin‐ ues running where it left off.

Response time guarantees

In some systems, there is a specified deadline by which the software must respond; if it doesn’t meet the deadline, that may cause a failure of the entire system. These are so-called hard real-time systems.

Providing real-time guarantees in a system requires support from all levels of the software stack: a real-time operating system (RTOS) that allows processes to be scheduled with a guaranteed allocation of CPU time in specified intervals is needed; library functions must document their worst-case execution times; dynamic memory allocation may be restricted or disallowed entirely.

Limiting the impact of garbage collection

An emerging idea is to treat GC pauses like brief planned outages of a node, and to let other nodes handle requests from clients while one node is collecting its garbage. If the runtime can warn the application that a node soon requires a GC pause, the application can stop sending new requests to that node, wait for it to finish processing outstanding requests, and then perform the GC while no requests are in progress.

A variant of this idea is to use the garbage collector only for short-lived objects (which are fast to collect) and to restart processes periodically, before they accumulate enough long-lived objects to require a full GC of long-lived objects. One node can be restarted at a time, and traffic can be shifted away from the node before the planned restart, like in a rolling upgrade.

Knowledge, Truth, and Lies

So far in this chapter we have explored the ways in which distributed systems are different from programs running on a single computer: there is no shared memory, only message passing via an unreliable network with variable delays, and the systems may suffer from partial failures, unreliable clocks, and processing pauses.

The Truth Is Defined by the Majority

A distributed system cannot exclusively rely on a single node, because a node may fail at any time, potentially leaving the system stuck and unable to recover. Instead, many distributed algorithms rely on a quorum, that is, voting among the nodes: decisions require some minimum number of votes from several nodes in order to reduce the dependence on any one particular node.

There can only be only one majority in the system—there cannot be two majorities with conflicting decisions at the same time.

The leader and the lock

Frequently, a system requires there to be only one of some thing:

- Only one node is allowed to be the leader for a database partition, to avoid split brain.

- Only one transaction or client is allowed to hold the lock for a particular resource or object, to prevent concurrently writing to it and corrupting it.

- Only one user is allowed to register a particular username, because a username must uniquely identify a user.

If a node continues acting as the chosen one, even though the majority of nodes have declared it dead, it could cause problems in a system that is not carefully designed. Such a node could send messages to other nodes in its self-appointed capacity, and if other nodes believe it, the system as a whole may do something incorrect.

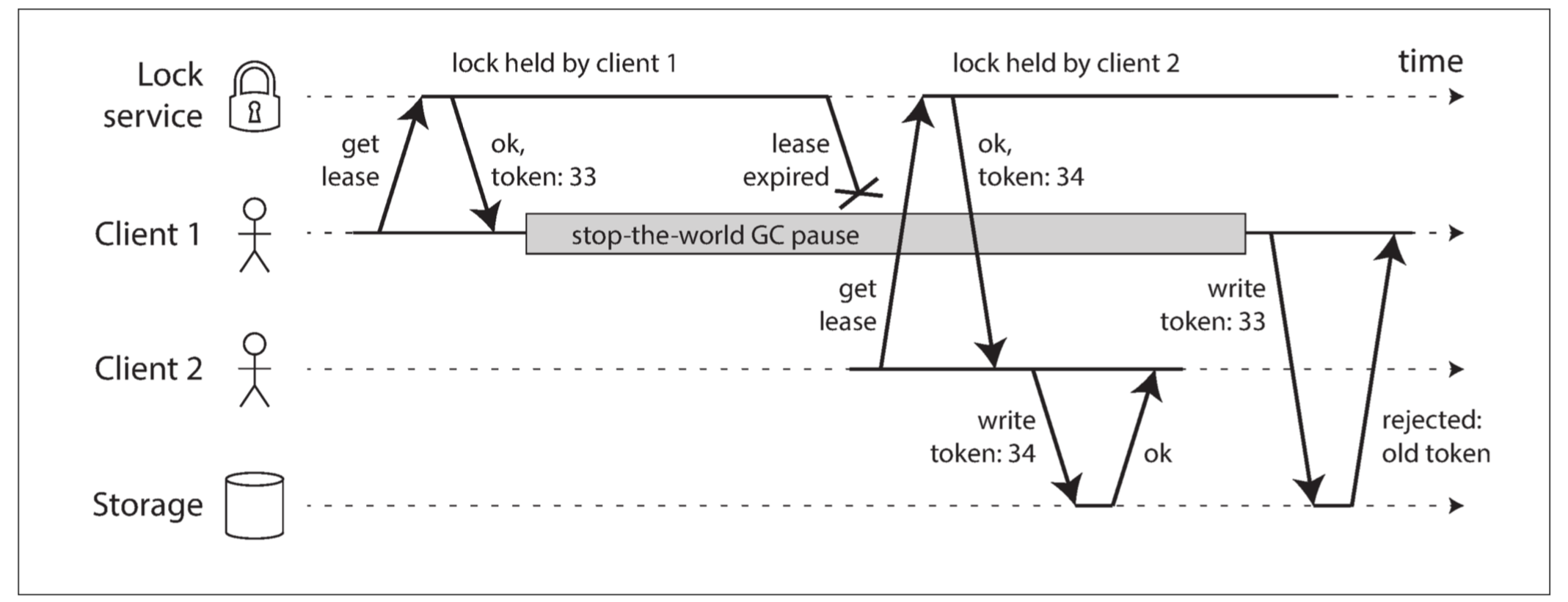

Fencing tokens

we need to ensure that a node that is under a false belief of being “the chosen one” cannot disrupt the rest of the system. A fairly simple technique that achieves this goal is called fencing:

If ZooKeeper is used as lock service, the transaction ID zxid or the node version cversion can be used as fencing token. Since they are guaranteed to be monotonically increasing, they have the required properties.

Checking a token on the server side may seem like a downside, but it is arguably a good thing: it is unwise for a service to assume that its clients will always be well behaved, because the clients are often run by people whose priorities are very different from the priorities of the people running the service

Byzantine Faults

Distributed systems problems become much harder if there is a risk that nodes may “lie” (send arbitrary faulty or corrupted responses)—for example, if a node may claim to have received a particular message when in fact it didn’t. Such behavior is known as a Byzantine fault, and the problem of reaching consensus in this untrusting environment is known as the Byzantine Generals Problem.

Weak forms of lying

Although we assume that nodes are generally honest, it can be worth adding mechanisms to software that guard against weak forms of “lying”—for example, invalid messages due to hardware issues, software bugs, and misconfiguration.

-

Network packets do sometimes get corrupted due to hardware issues or bugs in operating systems, drivers, routers, etc. Usually, corrupted packets are caught by the checksums built into TCP and UDP, but sometimes they evade detection.

-

A publicly accessible application must carefully sanitize any inputs from users, for example checking that a value is within a reasonable range and limiting the size of strings to prevent denial of service through large memory allocations.

-

NTP clients can be configured with multiple server addresses. When synchronizing, the client contacts all of them, estimates their errors, and checks that a majority of servers agree on some time range. As long as most of the servers are okay, a misconfigured NTP server that is reporting an incorrect time is detected as an outlier and is excluded from synchronization.

System Model and Reality

Algorithms need to be written in a way that does not depend too heavily on the details of the hardware and software configuration on which they are run. This in turn requires that we somehow formalize the kinds of faults that we expect to happen in a system. We do this by defining a system model, which is an abstraction that describes what things an algorithm may assume.

With regard to timing assumptions, three system models are in common use:

-

Synchronous model

The synchronous model assumes bounded network delay, bounded process pauses, and bounded clock error. This does not imply exactly synchronized clocks or zero network delay; it just means you know that network delay, pauses, and clock drift will never exceed some fixed upper bound. The synchronous model is not a realistic model of most practical systems, because unbounded delays and pauses do occur.

-

Partially synchronous model

Partial synchrony means that a system behaves like a synchronous system most of the time, but it sometimes exceeds the bounds for network delay, process pauses, and clock drift.

-

Asynchronous model

In this model, an algorithm is not allowed to make any timing assumptions—in fact, it does not even have a clock (so it cannot use timeouts).

Moreover, besides timing issues, we have to consider node failures. The three most common system models for nodes are:

-

Crash-stop faults

In the crash-stop model, an algorithm may assume that a node can fail in only one way, namely by crashing. This means that the node may suddenly stop responding at any moment, and thereafter that node is gone forever—it never comes back.

-

Crash-recovery faults

We assume that nodes may crash at any moment, and perhaps start responding again after some unknown time. In the crash-recovery model, nodes are assumed to have stable storage (i.e., nonvolatile disk storage) that is preserved across crashes, while the in-memory state is assumed to be lost.

-

Byzantine (arbitrary) faults

Nodes may do absolutely anything, including trying to trick and deceive other nodes, as described in the last section.

Correctness of an algorithm

To define what it means for an algorithm to be correct, we can describe its properties.

We can write down the properties we want of a distributed algorithm to define what it means to be correct. For example, if we are generating fencing tokens for a lock, we may require the algorithm to have the following properties:

-

Uniqueness

No two requests for a fencing token return the same value.

-

Monotonic sequence

If request x returned token tx, and request y returned token ty, and x completed before y began, then tx < ty.

-

Availability

A node that requests a fencing token and does not crash eventually receives a response.

An algorithm is correct in some system model if it always satisfies its properties in all situations that we assume may occur in that system model.

Safety and liveness

To clarify the situation, it is worth distinguishing between two different kinds of properties: safety and liveness properties.

Safety is often informally defined as nothing bad happens, and liveness as something good eventually happens.

The actual definitions of safety and liveness are precise and mathematical:

-

If a safety property is violated, we can point at a particular point in time at which it was broken. After a safety property has been violated, the violation cannot be undone—the damage is already done.

-

A liveness property works the other way round: it may not hold at some point in time (for example, a node may have sent a request but not yet received a response), but there is always hope that it may be satisfied in the future (namely by receiving a response).

Chapter 9. Consistency and Consensus

The best way of building fault-tolerant systems is to find some general-purpose abstractions with useful guarantees, implement them once, and then let applications rely on those guarantees. This is the same approach as we used with transactions.

One of the most important abstractions for distributed systems is consensus: that is, getting all of the nodes to agree on something.

Consistency Guarantees

There is some similarity between distributed consistency models and the hierarchy of transaction isolation levels we discussed previously. But while there is some overlap, they are mostly independent concerns: transaction isolation is primarily about avoiding race conditions due to concurrently executing transactions, whereas distributed consistency is mostly about coordinating the state of replicas in the face of delays and faults.

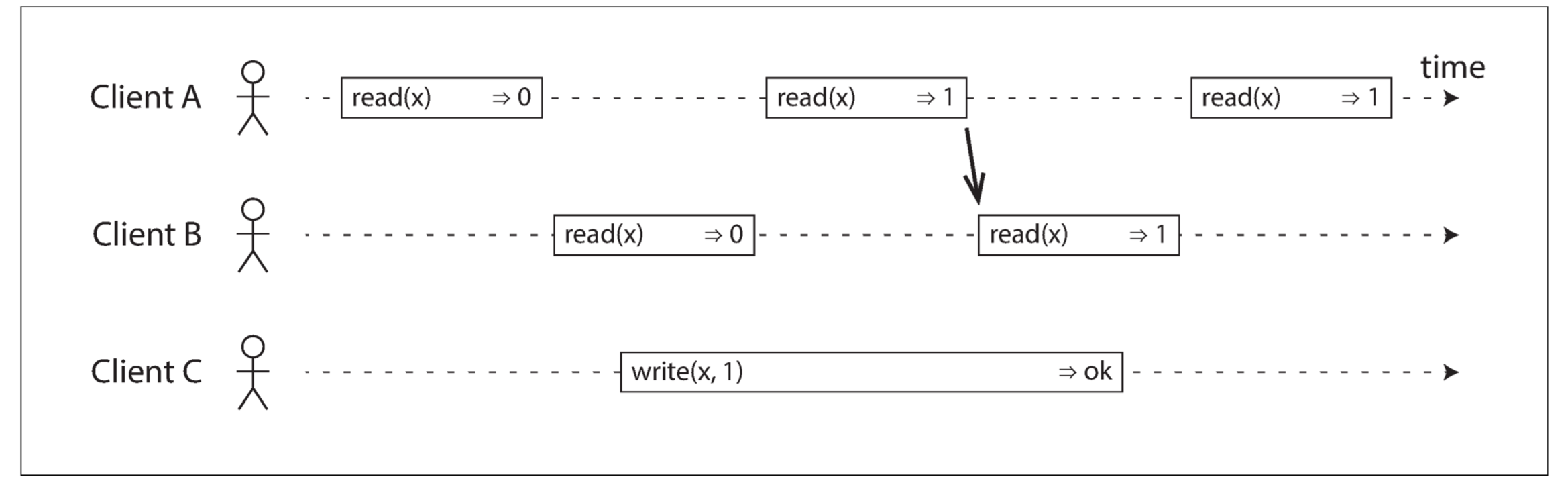

Linearizability

In a linearizable system, as soon as one client successfully completes a write, all clients reading from the database must be able to see the value just written. Maintaining the illusion of a single copy of the data means guaranteeing that the value read is the most recent, up-to-date value, and doesn’t come from a stale cache or replica. In other words, linearizability is a recency guarantee.

What Makes a System Linearizable?

In a linearizable system we imagine that there must be some point in time (between the start and end of the write operation) at which the value of x atomically flips from 0 to 1. Thus, if one client’s read returns the new value 1, all subsequent reads must also return the new value, even if the write operation has not yet completed.

Linearizability Versus Serializability

Serializability is an isolation property of transactions. It guarantees that transactions behave the same as if they had executed in some serial order (each transaction running to completion before the next transaction starts). It is okay for that serial order to be different from the order in which transactions were actually run. Linearizability is a recency guarantee on reads and writes of a register (an individual object). It doesn’t group operations together into transactions, so it does not prevent problems such as write skew. A database may provide both serializability and linearizability, and this combination is known as strict serializability or strong one-copy serializability.

Implementations of serializability based on two-phase locking or actual serial execution are typically linearizable.

However, serializable snapshot isolation is not linearizable: by design, it makes reads from a consistent snapshot, to avoid lock contention between readers and writers.

Implementing Linearizable Systems

Since linearizability essentially means “behave as though there is only a single copy of the data, and all operations on it are atomic,” the simplest answer would be to really only use a single copy of the data. However, that approach would not be able to tolerate faults: if the node holding that one copy failed, the data would be lost, or at least inaccessible until the node was brought up again. The most common approach to making a system fault-tolerant is to use replication.

Let’s revisit the replication methods from Chapter 5, and compare whether they can be made linearizable:

-

Single-leader replication (potentially linearizable)

With asynchronous replication, failover may even lose committed writes, which violates both durability and linearizability.

-

Consensus algorithms (linearizable)

Some consensus algorithms, which we will discuss later in this chapter, bear a resemblance to single-leader replication. However, consensus protocols contain measures to prevent split brain and stale replicas. Thanks to these details, consensus algorithms can implement linearizable storage safely.

-

Multi-leader replication (not linearizable)

Systems with multi-leader replication are generally not linearizable, because they concurrently process writes on multiple nodes and asynchronously replicate them to other nodes. For this reason, they can produce conflicting writes that require resolution. Such conflicts are an artifact of the lack of a single copy of the data.

-

Leaderless replication (probably not linearizable)

For systems with leaderless replication (Dynamo-style), people sometimes claim that you can obtain “strong consistency” by requiring quorum reads and writes (w + r > n). Depending on the exact configuration of the quorums, and depending on how you define strong consistency, this is not quite true. Even with strict quorums, nonlinearizable behavior is possible, as demonstrated in the next section.

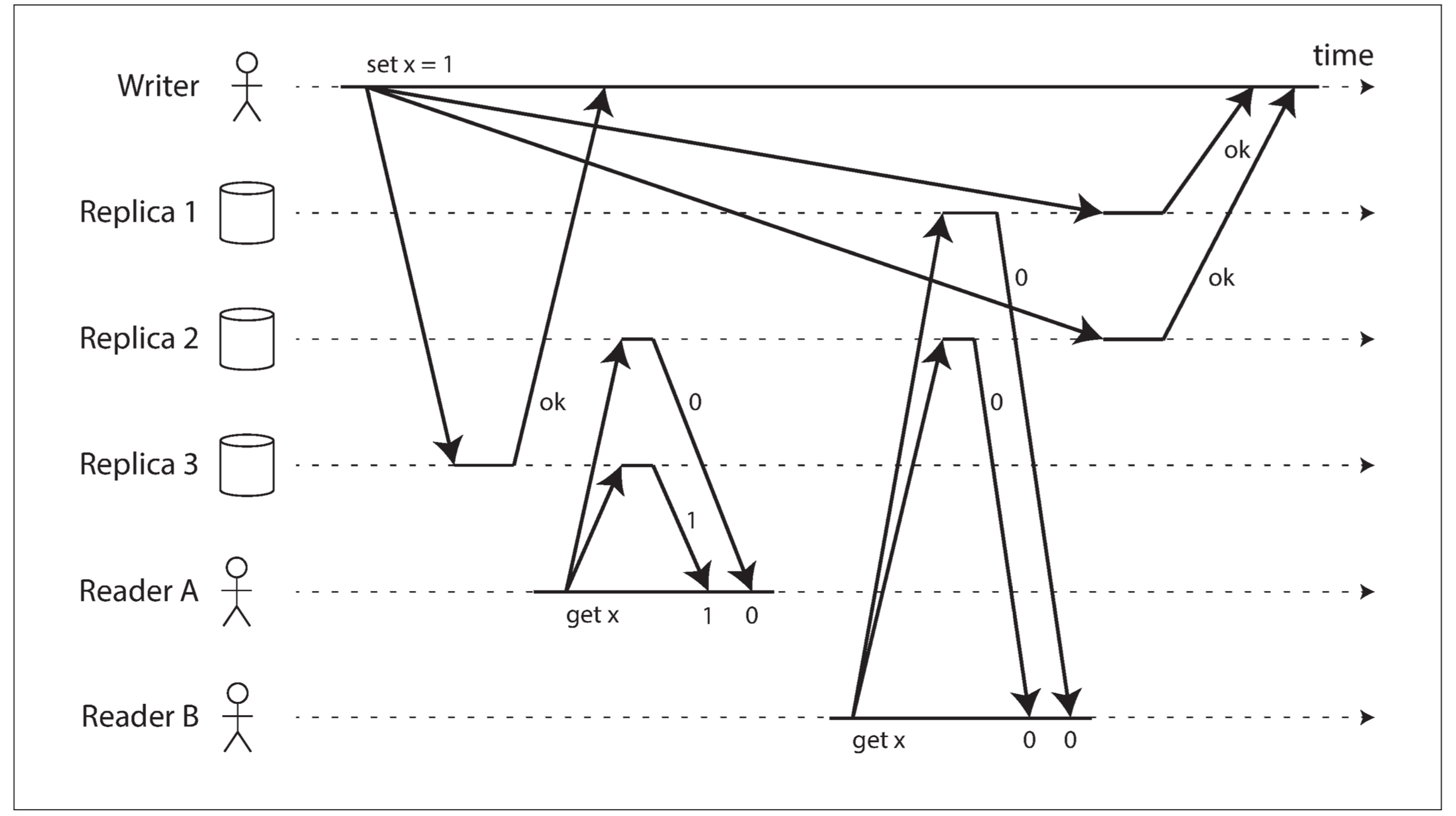

Linearizability and quorums

Intuitively, it seems as though strict quorum reads and writes should be linearizable in a Dynamo-style model. However, when we have variable network delays, it is possible to have race conditions:

The quorum condition is met (w + r > n), but this execution is nevertheless not linearizable: B’s request begins after A’s request completes, but B returns the old value while A returns the new value.

Interestingly, it is possible to make Dynamo-style quorums linearizable at the cost of reduced performance: a reader must perform read repair synchronously, before returning results to the application, and a writer must read the latest state of a quorum of nodes before sending its writes. However, Riak does not perform synchronous read repair due to the performance penalty. Cassandra does wait for read repair to complete on quorum reads, but it loses linearizability if there are multiple concurrent writes to the same key, due to its use of last-write-wins conflict resolution.

Moreover, only linearizable read and write operations can be implemented in this way; a linearizable compare-and-set operation cannot, because it requires a consensus algorithm.

In summary, it is safest to assume that a leaderless system with Dynamo-style replication does not provide linearizability.

The Cost of Linearizability

The CAP theorem

The trade-off is as follows:

-

If your application requires linearizability, and some replicas are disconnected from the other replicas due to a network problem, then some replicas cannot process requests while they are disconnected: they must either wait until the network problem is fixed, or return an error.

-

If your application does not require linearizability, then it can be written in a way that each replica can process requests independently, even if it is disconnected from other replicas (e.g., multi-leader). In this case, the application can remain available in the face of a network problem, but its behavior is not linearizable.

Thus, applications that don’t require linearizability can be more tolerant of network problems. This insight is popularly known as the CAP theorem.

Ordering Guarantees

We said previously that a linearizable register behaves as if there is only a single copy of the data, and that every operation appears to take effect atomically at one point in time. This definition implies that operations are executed in some well-defined order.

It turns out that there are deep connections between ordering, linearizability, and consensus.

Ordering and Causality

There are several reasons why ordering keeps coming up, and one of the reasons is that it helps preserve causality.

If a system obeys the ordering imposed by causality, we say that it is causally consistent. For example, snapshot isolation provides causal consistency: when you read from the database, and you see some piece of data, then you must also be able to see any data that causally precedes it.

The causal order is not a total order

A total order allows any two elements to be compared, so if you have two elements, you can always say which one is greater and which one is smaller.

However, mathematical sets are not totally ordered: is {a, b} greater than {b, c}? Well, you can’t really compare them, because neither is a subset of the other. We say they are incomparable, and therefore mathematical sets are partially ordered: in some cases one set is greater than another (if one set contains all the elements of another), but in other cases they are incomparable.

The difference between a total order and a partial order is reflected in different database consistency models:

-

Linearizability

In a linearizable system, we have a total order of operations: if the system behaves as if there is only a single copy of the data, and every operation is atomic, this means that for any two operations we can always say which one happened first.

-

Causality

We said that two operations are concurrent if neither happened before the other. Put another way, two events are ordered if they are causally related (one happened before the other), but they are incomparable if they are concurrent. This means that causality defines a partial order, not a total order: some operations are ordered with respect to each other, but some are incomparable.

Therefore, according to this definition, there are no concurrent operations in a linearizable datastore: there must be a single timeline along which all operations are totally ordered.

Concurrency would mean that the timeline branches and merges again—and in this case, operations on different branches are incomparable.

Linearizability is stronger than causal consistency

Linearizability implies causality: any system that is linearizable will preserve causality correctly.

Causal consistency is the strongest possible consistency model that does not slow down due to network delays, and remains available in the face of network failures.

In many cases, systems that appear to require linearizability in fact only really require causal consistency, which can be implemented more efficiently. Based on this observation, researchers are exploring new kinds of databases that preserve causality, with performance and availability characteristics that are similar to those of eventually consistent systems.

Capturing causal dependencies

In order to maintain causality, you need to know which operation happened before which other operation. This is a partial order: concurrent operations may be processed in any order, but if one operation happened before another, then they must be processed in that order on every replica. Thus, when a replica processes an operation, it must ensure that all causally preceding operations (all operations that happened before) have already been processed; if some preceding operation is missing, the later operation must wait until the preceding operation has been processed.

Causal consistency it needs to track causal dependencies across the entire database, not just for a single key. Version vectors can be generalized to do this.

In order to determine the causal ordering, the database needs to know which version of the data was read by the application. A similar idea appears in the conflict detection of SSI: when a transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether the version of the data that it read is still up to date. To this end, the database keeps track of which data has been read by which transaction.

Sequence Number Ordering

Although causality is an important theoretical concept, actually keeping track of all causal dependencies can become impractical. In many applications, clients read lots of data before writing something, and then it is not clear whether the write is causally dependent on all or only some of those prior reads. Explicitly tracking all the data that has been read would mean a large overhead.

However, there is a better way: we can use sequence numbers or timestamps to order events. A timestamp need not come from a time-of-day clock (or physical clock, which have many problems). It can instead come from a logical clock, which is an algorithm to generate a sequence of numbers to identify operations, typically using counters that are incremented for every operation.

Such sequence numbers or timestamps are compact (only a few bytes in size), and they provide a total order: that is, every operation has a unique sequence number, and you can always compare two sequence numbers to determine which is greater.

In a database with single-leader replication, the replication log defines a total order of write operations that is consistent with causality. The leader can simply increment a counter for each operation, and thus assign a monotonically increasing sequence number to each operation in the replication log. If a follower applies the writes in the order they appear in the replication log, the state of the follower is always causally consistent

Noncausal sequence number generators

If there is not a single leader (perhaps because you are using a multi-leader or leaderless database, or because the database is partitioned), it is less clear how to generate sequence numbers for operations. Various methods are used in practice:

-

Each node can generate its own independent set of sequence numbers. For example, if you have two nodes, one node can generate only odd numbers and the other only even numbers.

-

You can attach a timestamp from a time-of-day clock (physical clock) to each operation. Such timestamps are not sequential, but if they have sufficiently high resolution, they might be sufficient to totally order operations. This fact is used in the last write wins conflict resolution method.

-

You can preallocate blocks of sequence numbers.

However, they all have a problem: the sequence numbers they generate are not consistent with causality.

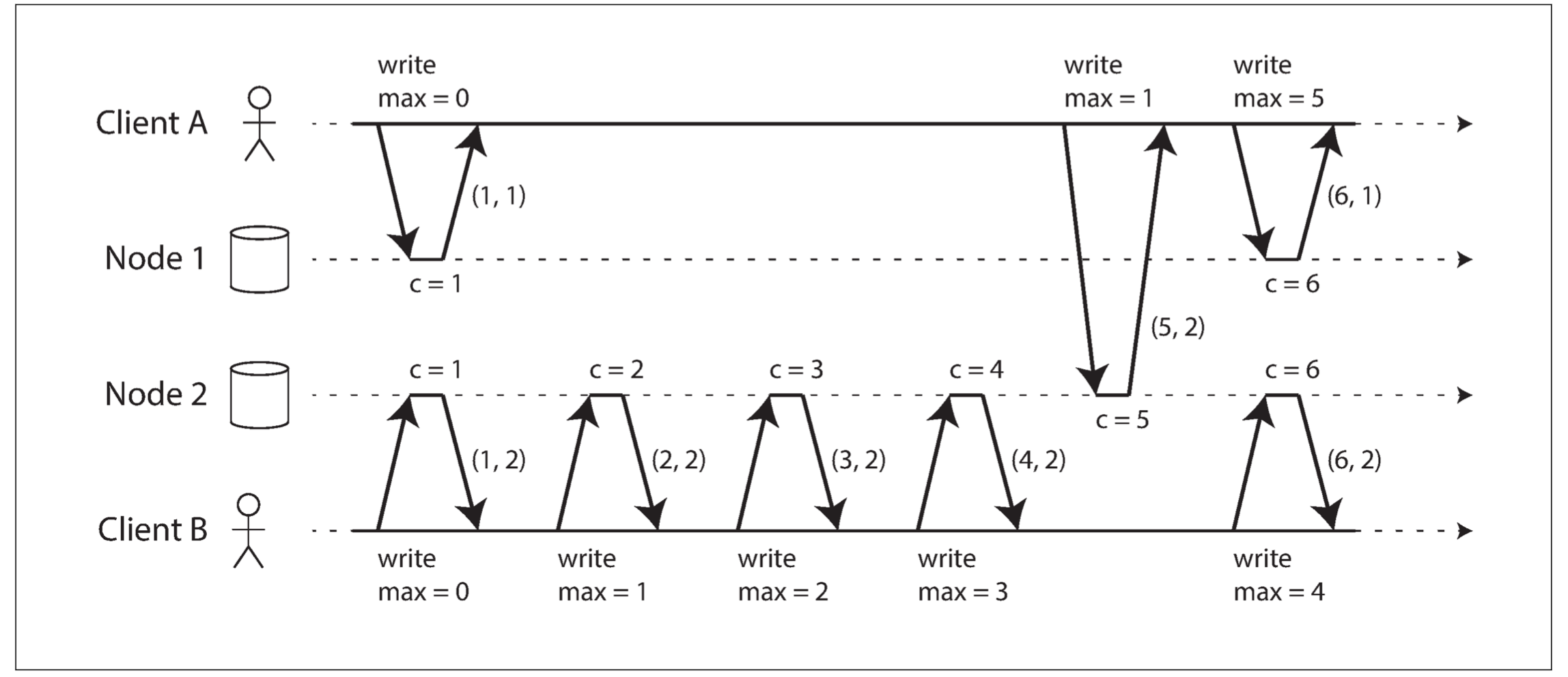

Lamport timestamps

Although the three sequence number generators just described are inconsistent with causality, there is actually a simple method for generating sequence numbers that is consistent with causality. It is called a Lamport timestamp.

The use of Lamport timestamps is illustrated in following figure. Each node has a unique identifier, and each node keeps a counter of the number of operations it has processed. The Lamport timestamp is then simply a pair of (counter, node ID). Two nodes may sometimes have the same counter value, but by including the node ID in the timestamp, each timestamp is made unique.

A Lamport timestamp bears no relationship to a physical time-of-day clock, but it provides total ordering: if you have two timestamps, the one with a greater counter value is the greater timestamp; if the counter values are the same, the one with the greater node ID is the greater timestamp.

The key idea about Lamport timestamps, which makes them consistent with causality, is the following: every node and every client keeps track of the maximum counter value it has seen so far, and includes that maximum on every request. When a node receives a request or response with a maximum counter value greater than its own counter value, it immediately increases its own counter to that maximum.

Lamport timestamps are sometimes confused with version vectors. Although there are some similarities, they have a different purpose: version vectors can distinguish whether two operations are concurrent or whether one is causally dependent on the other, whereas Lamport timestamps always enforce a total ordering.

Timestamp ordering is not sufficient

Although Lamport timestamps define a total order of operations that is consistent with causality, they are not quite sufficient to solve many common problems in distributed systems.

The problem here is that the total order of operations only emerges after you have collected all of the operations. If another node has generated some operations, but you don’t yet know what they are, you cannot construct the final ordering of operations: the unknown operations from the other node may need to be inserted at various positions in the total order.

To conclude: in order to implement something like a uniqueness constraint for usernames, it’s not sufficient to have a total ordering of operations—you also need to know when that order is finalized.

This idea of knowing when your total order is finalized is captured in the topic of total order broadcast.

Total Order Broadcast

In the last section we discussed ordering by timestamps or sequence numbers, but found that it is not as powerful as single-leader replication. Single-leader replication determines a total order of operations by choosing one node as the leader and sequencing all operations on a single CPU core on the leader. The challenge then is how to scale the system if the throughput is greater than a single leader can handle, and also how to handle failover if the leader fails. In the distributed systems literature, this problem is known as total order broadcast or atomic broadcast.

Total order broadcast is usually described as a protocol for exchanging messages between nodes. Informally, it requires that two safety properties always be satisfied:

-

Reliable delivery

No messages are lost: if a message is delivered to one node, it is delivered to all nodes.

-

Totally ordered delivery

Messages are delivered to every node in the same order.

A correct algorithm for total order broadcast must ensure that the reliability and ordering properties are always satisfied, even if a node or the network is faulty.

Using total order broadcast

Consensus services such as ZooKeeper and etcd actually implement total order broadcast. This fact is a hint that there is a strong connection between total order broadcast and consensus.

Total order broadcast is exactly what you need for database replication: if every message represents a write to the database, and every replica processes the same writes in the same order, then the replicas will remain consistent with each other (aside from any temporary replication lag). This principle is known as state machine replication.

Similarly, total order broadcast can be used to implement serializable transactions, if every message represents a deterministic transaction to be executed as a stored procedure, and if every node processes those messages in the same order, then the partitions and replicas of the database are kept consistent with each other.

An important aspect of total order broadcast is that the order is fixed at the time the messages are delivered: a node is not allowed to retroactively insert a message into an earlier position in the order if subsequent messages have already been delivered. This fact makes total order broadcast stronger than timestamp ordering.

Another way of looking at total order broadcast is that it is a way of creating a log (as in a replication log, transaction log, or write-ahead log): delivering a message is like appending to the log. Since all nodes must deliver the same messages in the same order, all nodes can read the log and see the same sequence of messages.

Total order broadcast is also useful for implementing a lock service that provides fencing tokens. Every request to acquire the lock is appended as a message to the log, and all messages are sequentially numbered in the order they appear in the log. The sequence number can then serve as a fencing token, because it is monotonically increasing. In ZooKeeper, this sequence number is called zxid.

Implementing linearizable storage using total order broadcast

Total order broadcast is asynchronous: messages are guaranteed to be delivered reliably in a fixed order, but there is no guarantee about when a message will be delivered (so one recipient may lag behind the others). By contrast, linearizability is a recency guarantee: a read is guaranteed to see the latest value written.

However, if you have total order broadcast, you can build linearizable storage on top of it.

Because log entries are delivered to all nodes in the same order, if there are several concurrent writes, all nodes will agree on which one came first. Choosing the first of the conflicting writes as the winner and aborting later ones ensures that all nodes agree on whether a write was committed or aborted. A similar approach can be used to implement serializable multi-object transactions on top of a log.

While this procedure ensures linearizable writes, it doesn’t guarantee linearizable reads—if you read from a store that is asynchronously updated from the log, it may be stale. To make reads linearizable, there are a few options:

-

You can sequence reads through the log by appending a message, reading the log, and performing the actual read when the message is delivered back to you. The message’s position in the log thus defines the point in time at which the read happens.

-

If the log allows you to fetch the position of the latest log message in a linearizable way, you can query that position, wait for all entries up to that position to be delivered to you, and then perform the read.

-

You can make your read from a replica that is synchronously updated on writes, and is thus sure to be up to date.

Distributed Transactions and Consensus

Consensus is one of the most important and fundamental problems in distributed computing. On the surface, it seems simple: informally, the goal is simply to get several nodes to agree on something. There are a number of situations in which it is important for nodes to agree. For example:

-

Leader election

The leadership position might become contested if some nodes can’t communicate with others due to a network fault. In this case, consensus is important to avoid a bad failover, resulting in a split brain situation in which two nodes both believe themselves to be the leader.

-

Atomic commit

In a database that supports transactions spanning several nodes or partitions, we have the problem that a transaction may fail on some nodes but succeed on others. If we want to maintain transaction atomicity (in the sense of ACID), we have to get all nodes to agree on the outcome of the transaction: either they all abort/roll back (if anything goes wrong) or they all commit (if nothing goes wrong). This instance of consensus is known as the atomic commit problem.

Atomic Commit and Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

From single-node to distributed atomic commit

For transactions that execute at a single database node, atomicity is commonly implemented by the storage engine.

However, what if multiple nodes are involved in a transaction? In these cases, it is not sufficient to simply send a commit request to all of the nodes and independently commit the transaction on each one.

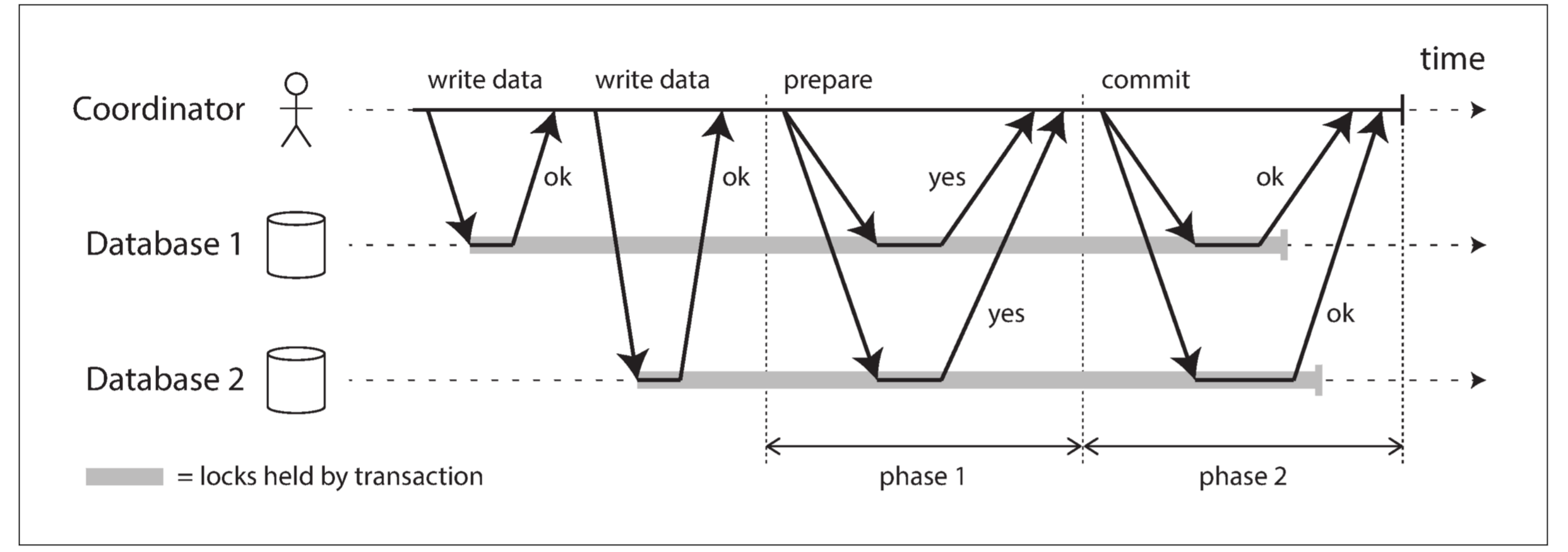

Introduction to two-phase commit

Two-phase commit is an algorithm for achieving atomic transaction commit across multiple nodes. Instead of a single commit request, as with a single-node transaction, the commit/abort process in 2PC is split into two phases (hence the name):

2PC uses a new component that does not normally appear in single-node transactions: a coordinator (also known as transaction manager). The coordinator is often implemented as a library within the same application process that is requesting the transaction, but it can also be a separate process or service.

When the application is ready to commit, the coordinator begins phase 1: it sends a prepare request to each of the nodes, asking them whether they are able to commit. The coordinator then tracks the responses from the participants:

-

If all participants reply “yes,” indicating they are ready to commit, then the coordinator sends out a commit request in phase 2, and the commit actually takes place.

-

If any of the participants replies “no,” the coordinator sends an abort request to all nodes in phase 2.

A system of promises

To understand why it works, we have to break down the process in a bit more detail:

-

When the application wants to begin a distributed transaction, it requests a transaction ID from the coordinator. This transaction ID is globally unique.

-

The application begins a single-node transaction on each of the participants, and attaches the globally unique transaction ID to the single-node transaction. All reads and writes are done in one of these single-node transactions. If anything goes wrong at this stage (for example, a node crashes or a request times out), the coordinator or any of the participants can abort.

-

When a participant receives the prepare request, it makes sure that it can definitely commit the transaction under all circumstances. This includes writing all transaction data to disk (a crash, a power failure, or running out of disk space is not an acceptable excuse for refusing to commit later), and checking for any conflicts or constraint violations. By replying “yes” to the coordinator, the node promises to commit the transaction without error if requested. In other words, the participant surrenders the right to abort the transaction, but without actually committing it.

-

When the coordinator has received responses to all prepare requests, it makes a definitive decision on whether to commit or abort the transaction (committing only if all participants voted “yes”). The coordinator must write that decision to its transaction log on disk so that it knows which way it decided in case it subsequently crashes. This is called the commit point.

-

Once the coordinator’s decision has been written to disk, the commit or abort request is sent to all participants. If this request fails or times out, the coordinator must retry forever until it succeeds. There is no more going back: if the decision was to commit, that decision must be enforced, no matter how many retries it takes.

Coordinator failure

If the coordinator fails before sending the prepare requests, a participant can safely abort the transaction. But once the participant has received a prepare request and voted “yes,” it can no longer abort unilaterally—it must wait to hear back from the coordinator whether the transaction was committed or aborted. If the coordinator crashes or the network fails at this point, the participant can do nothing but wait.

When the coordinator recovers, it determines the status of all in-doubt transactions by reading its transaction log. Any transactions that don’t have a commit record in the coordinator’s log are aborted.

Three-phase commit

Two-phase commit is called a blocking atomic commit protocol due to the fact that 2PC can become stuck waiting for the coordinator to recover.

As an alternative to 2PC, an algorithm called three-phase commit (3PC) has been proposed. However, 3PC assumes a network with bounded delay and nodes with bounded response times; in most practical systems with unbounded network delay and process pauses, it cannot guarantee atomicity.

In general, nonblocking atomic commit requires a perfect failure detector— i.e., a reliable mechanism for telling whether a node has crashed or not. In a network with unbounded delay a timeout is not a reliable failure detector, because a request may time out due to a network problem even if no node has crashed.

Distributed Transactions in Practice

Two quite different types of distributed transactions are often conflated:

-

Database-internal distributed transactions

Some distributed databases support internal transactions among the nodes of that database. In this case, all the nodes participating in the transaction are running the same database software.

-

Heterogeneous distributed transactions

In a heterogeneous transaction, the participants are two or more different technologies. A distributed transaction across these systems must ensure atomic commit, even though the systems may be entirely different under the hood.

Holding locks while in doubt

Why do we care so much about a transaction being stuck in doubt? The problem is with locking. The database cannot release those locks until the transaction commits or aborts.

Recovering from coordinator failure

In practice, orphaned in-doubt transactions do occur—that is, transactions for which the coordinator cannot decide the outcome for whatever reason (e.g., because the transaction log has been lost or corrupted due to a software bug). These transactions cannot be resolved automatically, so they sit forever in the database, holding locks and blocking other transactions.

The only way out is for an administrator to manually decide whether to commit or roll back the transactions. The administrator must examine the participants of each in-doubt transaction, determine whether any participant has committed or aborted already, and then apply the same outcome to the other participants.

Limitations of distributed transactions

XA transactions solve the real and important problem of keeping several participant data systems consistent with each other, but as we have seen, they also introduce major operational problems. In particular, the key realization is that the transaction coordinator is itself a kind of database (in which transaction outcomes are stored), and so it needs to be approached with the same care as any other important database:

-

If the coordinator is not replicated but runs only on a single machine, it is a single point of failure for the entire system.

-

Many server-side applications are developed in a stateless model (as favored by HTTP), with all persistent state stored in a database, which has the advantage. that application servers can be added and removed at will. However, when the coordinator is part of the application server, it changes the nature of the deployment. Suddenly, the coordinator’s logs become a crucial part of the durable system state—as important as the databases themselves, since the coordinator logs are required in order to recover in-doubt transactions after a crash. Such application servers are no longer stateless.

-

Since XA needs to be compatible with a wide range of data systems, it is necessarily a lowest common denominator. For example, it cannot detect deadlocks across different systems (since that would require a standardized protocol for systems to exchange information on the locks that each transaction is waiting for), and it does not work with SSI, since that would require a protocol for identifying conflicts across different systems.

-

For database-internal distributed transactions (not XA), the limitations are not so great—for example, a distributed version of SSI is possible. However, there remains the problem that for 2PC to successfully commit a transaction, all participants must respond. Consequently, if any part of the system is broken, the transaction also fails. Distributed transactions thus have a tendency of amplifying failures, which runs counter to our goal of building fault-tolerant systems.

Fault-Tolerant Consensus

Informally, consensus means getting several nodes to agree on something. The consensus problem is normally formalized as follows: one or more nodes may propose values, and the consensus algorithm decides on one of those values.

In this formalism, a consensus algorithm must satisfy the following properties:

-

Uniform agreement

No two nodes decide differently.

-

Integrity

No node decides twice.

-

Validity

If a node decides value v, then v was proposed by some node.(v 一定是某个节点 propose 的)

-

Termination

Every node that does not crash eventually decides some value.

The uniform agreement and integrity properties define the core idea of consensus: everyone decides on the same outcome, and once you have decided, you cannot change your mind. The validity property exists mostly to rule out trivial solutions: for example, you could have an algorithm that always decides null, no matter what was proposed; this algorithm would satisfy the agreement and integrity properties, but not the validity property.

The termination property formalizes the idea of fault tolerance. It essentially says that a consensus algorithm cannot simply sit around and do nothing forever—in other words, it must make progress. Even if some nodes fail, the other nodes must still reach a decision.

Consensus algorithms and total order broadcast

Remember that total order broadcast requires messages to be delivered exactly once, in the same order, to all nodes. If you think about it, this is equivalent to performing several rounds of consensus: in each round, nodes propose the message that they want to send next, and then decide on the next message to be delivered in the total order.

So, total order broadcast is equivalent to repeated rounds of consensus (each consensus decision corresponding to one message delivery):

- Due to the agreement property of consensus, all nodes decide to deliver the same messages in the same order.

- Due to the integrity property, messages are not duplicated.

- Due to the validity property, messages are not corrupted and not fabricated out of thin air.

- Due to the termination property, messages are not lost.

Viewstamped Replication, Raft, and Zab implement total order broadcast directly, because that is more efficient than doing repeated rounds of one-value-at-a-time consensus. In the case of Paxos, this optimization is known as Multi-Paxos.

Epoch numbering and quorums

All of the consensus protocols discussed so far internally use a leader in some form or another, but they don’t guarantee that the leader is unique. Instead, they can make a weaker guarantee: the protocols define an epoch number (called the ballot number in Paxos, view number in Viewstamped Replication, and term number in Raft) and guarantee that within each epoch, the leader is unique.

Before a leader is allowed to decide anything, it must first check that there isn’t some other leader with a higher epoch number which might take a conflicting decision.

It must collect votes from a quorum of nodes. For every decision that a leader wants to make, it must send the proposed value to the other nodes and wait for a quorum of nodes to respond in favor of the proposal. The quorum typically, but not always, consists of a majority of nodes. A node votes in favor of a proposal only if it is not aware of any other leader with a higher epoch.

Limitations of consensus

The process by which nodes vote on proposals before they are decided is a kind of synchronous replication. Consensus systems always require a strict majority to operate. This means you need a minimum of three nodes in order to tolerate one failure.

Most consensus algorithms assume a fixed set of nodes that participate in voting, which means that you can’t just add or remove nodes in the cluster. Dynamic membership extensions to consensus algorithms allow the set of nodes in the cluster to change over time, but they are much less well understood than static membership algorithms.

Sometimes, consensus algorithms are particularly sensitive to network problems. For example, Raft has been shown to have unpleasant edge cases: if the entire network is working correctly except for one particular network link that is consistently unreliable, Raft can get into situations where leadership continually bounces between two nodes, or the current leader is continually forced to resign, so the system effectively never makes progress.

Membership and Coordination Services

ZooKeeper is modeled after Google’s Chubby lock service, implementing not only total order broadcast (and hence consensus), but also an interesting set of other features that turn out to be particularly useful when building distributed systems:

-

Linearizable atomic operations

Using an atomic compare-and-set operation, you can implement a lock. A distributed lock is usually implemented as a lease, which has an expiry time so that it is eventually released in case the client fails.

-

Total ordering of operations

The fencing token is some number that monotonically increases every time the lock is acquired. ZooKeeper provides this by totally ordering all operations and giving each operation a monotonically increasing transaction ID (zxid) and version number (cversion).

-

Failure detection

Clients maintain a long-lived session on ZooKeeper servers, and the client and server periodically exchange heartbeats to check that the other node is still alive. If the heartbeats cease for a duration that is longer than the session timeout, ZooKeeper declares the session to be dead. Any locks held by a session can be configured to be automatically released when the session times out (ZooKeeper calls these ephemeral nodes).

-

Change notifications

A client can find out when another client joins the cluster (based on the value it writes to ZooKeeper), or if another client fails (because its session times out and its ephemeral nodes disappear). By subscribing to notifications, a client avoids having to frequently poll to find out about changes.

Allocating work to nodes

An application may initially run only on a single node, but eventually may grow to thousands of nodes. Trying to perform majority votes over so many nodes would be terribly inefficient. Instead, ZooKeeper runs on a fixed number of nodes (usually three or five) and performs its majority votes among those nodes while supporting a potentially large number of clients. Thus, ZooKeeper provides a way of “outsourcing” some of the work of coordinating nodes (consensus, operation ordering, and failure detection) to an external service.

Service discovery

ZooKeeper, etcd, and Consul are also often used for service discovery—that is, to find out which IP address you need to connect to in order to reach a particular service.

Membership services

A membership service determines which nodes are currently active and live members of a cluster. It is nevertheless very useful for a system to have agreement on which nodes constitute the current membership. For example, choosing a leader could mean simply choosing the lowest-numbered among the current members, but this approach would not work if different nodes have divergent opinions on who the current members are.

Summary

We looked in depth at linearizability, a popular consistency model: its goal is to make replicated data appear as though there were only a single copy, and to make all operations act on it atomically.

Unlike linearizability, which puts all operations in a single, totally ordered timeline, causality provides us with a weaker consistency model: some things can be concurrent, so the version history is like a timeline with branching and merging. Causal consistency does not have the coordination overhead of linearizability and is much less sensitive to network problems.

However, even if we capture the causal ordering, we saw that some things cannot be implemented this way: we considered the example of ensuring that a username is unique and rejecting concurrent registrations for the same username. If one node is going to accept a registration, it needs to somehow know that another node isn’t concurrently in the process of registering the same name. This problem led us toward consensus.

We saw that achieving consensus means deciding something in such a way that all nodes agree on what was decided, and such that the decision is irrevocable.

Nevertheless, not every system necessarily requires consensus: for example, leaderless and multi-leader replication systems typically do not use global consensus. The conflicts that occur in these systems are a consequence of not having consensus across different leaders, but maybe that’s okay: maybe we simply need to cope without linearizability and learn to work better with data that has branching and merging version histories.